What we know (and what we don't) so far about the cyberattack on European airports

Summary

- Major European airports including Heathrow, Brussels, Berlin, and Dublin have reported disruptions in check-in, boarding, and kiosk systems. The outages have been linked to Collins Aerospace’s passenger processing platform MUSE, a system used across many international airports.

- The incident has been described as a ransomware attack in media reports citing the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity, though no official statement from the agency has been published.

- According to the National Crime Agency and later reported by BBC News, UK authorities arrested one suspect in West Sussex; the individual was later released on conditional bail. Investigations remain active.

- The variant behind the airport disruption has not been confirmed. Some reports have suggested HardBit, a closed ransomware operation active since 2022 that targets organizations directly.

- BlackBit and LokiLocker have also circulated in media and community discussions around the case, but these references appear speculative. BlackBit has been promoted as a small-scale Ransomware-as-a-Service, whereas LokiLocker looks more like a mislabel or fringe variant with little evidence of organized activity. At present, none of these families have been officially tied to the incident.

Unanswered Questions

- The ransomware variant has not been confirmed.

- The intrusion vector is unknown, including whether attackers compromised Collins Aerospace directly or gained access through a third-party supply chain.

- The full scope of affected airports and airlines has not been publicly disclosed, and the timeline for complete restoration remains unclear.

- It is not yet known whether data was exfiltrated, ransom demands were issued, or which actor type may be responsible, whether a criminal group, a state, or an insider.

Supermassive Black Hole: This Is Not the MUSE You Are Looking For

Collins Aerospace’s ARINC MUSE platform, offered today as vMUSE and cMUSE, allows multiple airlines to share check-in counters, kiosks, and boarding gates, reducing costs and making better use of limited space. vMUSE is the legacy model that airports run locally, while cMUSE is the modern, cloud-based version provided directly by Collins. Both improve efficiency, but cMUSE increases dependency on the vendor’s resilience. According to vendor material, hundreds of airlines and airports worldwide rely on MUSE, and in April 2025 Heathrow renewed its contract for cMUSE, which now supports more than 80 airlines across all four terminals.

In April 2025, Heathrow Airport renewed its contract with Collins Aerospace to continue using ARINC cMUSE across all terminals.

That efficiency comes with a risk. A shared platform creates a single point of failure. If MUSE is disrupted, the impact does not remain limited to one airline. Entire terminals slow down, flights are delayed or cancelled, and passengers face long lines as staff fall back to manual processes. A system created to support smooth travel can quickly turn into a bottleneck affecting thousands of passengers.

This is the core of a supply chain problem. Airports and airlines depend on a vendor’s software they cannot fully control. If attackers compromise that vendor or if the platform itself is disrupted, the impact cascades across every dependent organization.

The aviation sector has faced similar risks in the past, but the scope here is broader. In 2021, attackers compromised SITA, a major IT and passenger service provider, exposing data from frequent flyer programs across multiple airlines.

This year, Scattered Spider expanded its operations into the aviation sector, targeting outsourced IT providers and identity systems used by airlines and airport services. The group, long associated with social engineering and identity provider abuse, has shown signs of fragmentation and rebranding, with elements reportedly linked to Hunters International and remnants of Lapsus$. This fluid structure complicates attribution since the tactics associated with Scattered Spider continue even as the group evolves. While no evidence ties them directly to the airport disruption, their recent activity highlights the sector’s growing exposure to advanced criminal groups.

The Delhi Exception Paradox

Reports suggest that Delhi Airport uses the MUSE passenger processing software affected in Europe, while Goa, Hyderabad and other Indian airports run on different systems. Yet, according to the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, no impact was observed in India despite widespread outages at Heathrow, Brussels, and Berlin. This raises the question: why was Delhi spared while other airports keep facing the aftermath of the ransomware attack?

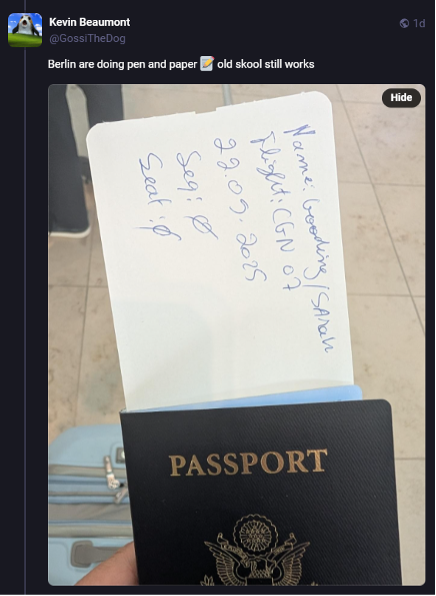

“Update: Unfortunately, there may continue to be delays and cancellations of flights at BER. Please check the flight status with your airline in advance and use the online check-in.” reports BER – Berlin Brandenburg Airport in their X account.

Delhi may have avoided disruption for several reasons. Its deployment of MUSE could be segmented or customized in ways that reduced exposure. The attackers themselves may have focused only on European instances, either to maximize impact or because only those deployments had a vulnerable setup. India’s IT Ministry responded swiftly after reports of the outages, instructing airports to review their systems, verify operational status, and intensify security monitoring.

Official Disclosure from RTX

On September 19, 2025, RTX Corporation filed a Form 8-K with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission acknowledging a ransomware incident affecting its MUSE passenger processing software. This marks the first official confirmation that the disruption involved ransomware and directly impacted systems used by airports.

U.S. companies are required to disclose significant events that could affect investors or operations. Cybersecurity incidents fall under this rule, and while RTX stated the MUSE ransomware attack is not expected to have a material financial impact, the company still had to formally notify regulators and the market.

SEC Form 8-K filed by RTX Corporation confirming a ransomware incident affecting its MUSE airport systems.

According to the filing:

“On September 19, 2025, RTX Corporation became aware of a product cybersecurity incident involving ransomware on systems that support its Multi-User System Environment (‘MUSE’) passenger processing software.”

RTX clarified that these systems are not part of its internal corporate network but instead run on customer-specific environments:

“The MUSE airport systems operate outside of the RTX enterprise network, residing on customer-specific networks.”

The company noted that affected customers switched to backup or manual processes, which resulted in flight delays and cancellations. RTX also emphasized that the disruption has not, at this stage, been financially significant:

“While our investigation and assessment of this product cybersecurity incident is ongoing, it has not had a material impact and is not reasonably expected to have a material impact on the Company’s financial condition, business operations or results of operations.”

RTX stated that it is working with internal and external cybersecurity experts, has contacted law enforcement and regulators, and is providing support to airlines and airports.

Transparency and Legal Obligations: How Disclosure Rules Differ for Airports

As a U.S.-listed company, RTX is subject to Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) rules that require prompt disclosure of cybersecurity incidents. This is why RTX filed a Form 8-K, confirming ransomware on its MUSE systems, even though it stressed the disruption was not expected to have a “material” financial impact.

In the EU, airports like Brussels and Berlin are covered by the NIS2 Directive, which since October 2024 has required them to report major cyber incidents to national regulators but not to the public unless authorities decide otherwise. In the UK, Heathrow is regulated under the older NIS framework, which requires reporting to the Civil Aviation Authority (CAA), and the National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC). If passenger data is exposed, the airport must also notify the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO), the UK’s data protection regulator. In both systems, operational outages are reported to regulators but do not have to be disclosed publicly.

This regulatory contrast explains the imbalance in available information. RTX’s SEC filing has provided clear, on-the-record confirmation of ransomware, while Heathrow and other airports have kept their public statements narrowly focused on service disruption and recovery. What the public sees is shaped less by the severity of the incident than by the jurisdiction’s disclosure regulations.

What Comes Next

RTX has now confirmed that the disruption was caused by a ransomware incident affecting its MUSE passenger processing software. Airports across Europe were forced to fall back on manual systems, resulting in delays and cancellations. Investigations are still underway, and no specific ransomware family or threat actor has been formally identified.

On X, researcher Cybersecurity Analyst and Security Researcher Dominic Alvieri noted reports suggesting Collins Aerospace was impacted by HardBit ransomware.

The attack highlights how far ransomware has evolved. The first known case, the AIDS Trojan in 1989, was primitive, spreading by floppy disks and demanding $189 to restore files. By the mid-2010s, ransomware groups were encrypting entire corporate networks. Soon after came double extortion, with attackers threatening to leak stolen data if victims refused to pay. Today, many groups have escalated to triple extortion, leveraging regulators, business partners, and even customers as additional pressure points. What began as a crude tactic has grown into a multi-billion-dollar criminal enterprise.

The aviation industry is especially exposed. Shared, outsourced systems like MUSE are designed for efficiency but also create common points of failure. A single disruption can ripple across multiple airports and airlines, grounding flights and stranding passengers far beyond the initial point of compromise.

If one supplier’s compromise can ripple across continents, how should regulators and airports rethink their dependence on outsourced platforms?